Jane Langton died last month, just short of her 96th birthday. Through 18 mysteries, her characters Homer and Mary Kelly studied transcendentalism while solving crimes. Langton wrote about the power of nature, art, and kindness. Her protagonists were often besotted with the natural world, or with art, while her villains and comically-awful annoyers were out of harmony with those worlds.

Though Langton hid clues and unveiled solutions, as the genre requires, her voice and presentations were utterly distinctive. She stitched plots together with quirky observations. A World War II-era University of Michigan alumna who studied astronomy and art history, Langton had prodigious powers of invention and spun plot complications from nuggets such as soil chemistry, the water table under a Boston church, and a flooded town under a reservoir. Her line drawings of the settings accompany most of the series, and the settings are integral to the stories.

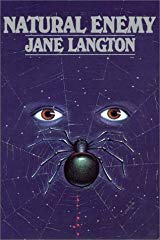

My favorite is her 1982 novel Natural Enemy. How do I love Natural Enemy? Let me count the ways. I love it for its texture, and the way she shifts from the greater picture to magnifying-glass detail. In the opening chapter, she zooms in from space to show Edward Heron dying, and eventually descends to the level of a barn spider. Weather reports pop up throughout the story, nudging the plot along.

My favorite is her 1982 novel Natural Enemy. How do I love Natural Enemy? Let me count the ways. I love it for its texture, and the way she shifts from the greater picture to magnifying-glass detail. In the opening chapter, she zooms in from space to show Edward Heron dying, and eventually descends to the level of a barn spider. Weather reports pop up throughout the story, nudging the plot along.

I love it for the protagonists. Homer, a detective before his scholarly career, can be a little goofy. Mary’s kindness and tact can get results that Homer can’t. “I gave her the jar of jelly, and she was pleased,” says Mary, about getting into a vital conversation. (I always pictured Mary looking rather like Langton.) “Mary is the sensible one,” Langton said on her Amazon page, “but I confess I like Homer’s rhapsodic flights of fancy.” He imagines privileged people: “They all lived in picture-book farmhouses, only every blade of grass was like a dollar bill, and the weathered fence rails were so much beaten silver.”

Their nephew John acts with gumption and teen-age gallantry. He works for Edward Heron’s daughters as they cope with the plant life that teems around them. He adores spiders and his employer Virginia. John’s enthusiasm for natural science gives him observational skills to complement his elders’. Virginia also has flights of fancy and writes “Letters to an Unknown Correspondent. Letters to the air.”

I love it for the pushy people and the bad guys: Buddy Whipple bulldozing the obstacles between himself and prosperity, grinning at a fatal asthma attack; Howard Croney seizing on a tragic plane crash to try to regain the governor’s office and pave more of the state; Dotty Gardenside crashing a funeral gathering to get a real-estate listing.

I love it for the sense of place. Concord and Lincoln, Massachusetts are dense with history, and even the flora, fauna, soil, and stone walls act on the characters.

I love it for the way Langton subverts conventions, such as that stuff about how you can’t have too many coincidences—say, a five-year-old with a photographic memory who fills in just when a witness is needed. And Langton doesn’t make you guess the murderer. She shows him at work. The suspense comes in the good guys’ efforts to thwart the terrible things happening in their small town.

Langton was brilliant not just in piecing together events and working out justice, but in comeuppance–truly poetic justice for the murderer and the conniving politician. Nature has no opinion about morality, but it provides clues to Buddy’s perfidy, and with a little help from a young science geek, the antidote to his murderous rage. Homer says of a key clue, “Only a spiderweb! Only a force of nature, like an earthquake or a tidal wave.”

**************

Nancy Shaw is the author of ten picture books, including the Sheep in a Jeep series, and an avid mystery reader. She lives in Ann Arbor, MI.

Nancy Shaw is the author of ten picture books, including the Sheep in a Jeep series, and an avid mystery reader. She lives in Ann Arbor, MI.