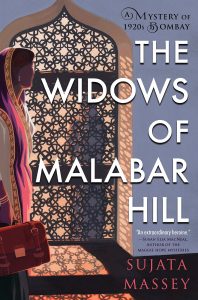

I was a totally geeked out fan of Sujata Massey’s Rei Shimura series about a Japanese American antiques dealer living in Japan. The books became progressively better and better as the series went forward, and Massey has apparently brought all the knowledge and expertise gained in writing those eleven books to good use in delivering this bravura work of historical fiction.

I was a totally geeked out fan of Sujata Massey’s Rei Shimura series about a Japanese American antiques dealer living in Japan. The books became progressively better and better as the series went forward, and Massey has apparently brought all the knowledge and expertise gained in writing those eleven books to good use in delivering this bravura work of historical fiction.

Set in 1920’s India, young Perveen Mistry is a lawyer – extremely unusual for the time and place – working for her father’s law firm, and though she’s not allowed to argue cases in court she can do all the research and contract work needed by the firm. Coming across her somewhat sparsely populated desk is the case of a will for three widows who were married to the same man. Their male agent has submitted documents stating that the women want to give up their inheritance and donate it to a charity instead, and the document is signed by all three.

Perveen is suspicious of the intent and the signatures – two of which look the same – so she asks her father if she can go and speak to the widows. They live in purdah and only communicate with males through a screen; by virtue of her gender, Perveen will have far greater access to the women. He reluctantly agrees and she goes to meet them.

She is far from charmed by the somewhat brutish male agent and goes to the other side of the house to meet the women. The oldest widow seems the most sophisticated; the second one has an advantage because she is the mother of the only son; and the third, an uneducated musician, is somewhat dismissed by the other two.

Perveen meets with them individually and something does indeed seem amiss regarding the will. When the agent is found dead – stabbed in the neck – on a subsequent visit the investigation naturally ramps up and involves Perveen’s father, the police, and a government official who lives up the street and happens to be the father of Perveen’s best friend from university.

The book has another mysterious thread involving Perveen herself. The narrative weaves back and forth between 1921 and 1916, when Perveen was meeting a young and handsome man. Part of the mystery of the book is in discovering how Perveen starts as a naive young woman and ends up as a lawyer.

In telling Perveen’s personal story, Massey illuminates her culture, as much as she does when she is telling the story of the widows living in Purdah. While I found the first chapter a little difficult with a swirl of unfamiliar names and different sectors in Indian culture and religious beliefs, by chapter two I was completely hooked.

This intimate novel is also a clever murder mystery and a look at Anglo-Indian culture from an almost epic perspective. Perveen is an incredibly appealing heroine and I am very much looking forward to book two, The Satapur Moonstone, which will be published in May.