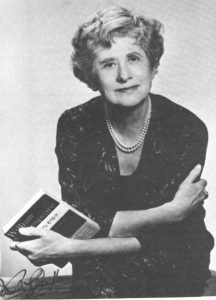

Ngaio Marsh (1895-1982), was one of the four cornerstones of British Crime fiction in the 30’s and 40’s, and that is reason enough to love her. Along with Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers and Margery Allingham, they were the original Queens of Crime, reshaping the puzzle based mystery and adding the bonus of continuing characters readers grew to love. Christie’s Poirot and Marple, Sayers’ Peter Wimsey, Allingham’s Albert Campion and Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn are some of the best known British detectives ever created.

Ngaio Marsh (1895-1982), was one of the four cornerstones of British Crime fiction in the 30’s and 40’s, and that is reason enough to love her. Along with Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers and Margery Allingham, they were the original Queens of Crime, reshaping the puzzle based mystery and adding the bonus of continuing characters readers grew to love. Christie’s Poirot and Marple, Sayers’ Peter Wimsey, Allingham’s Albert Campion and Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn are some of the best known British detectives ever created.

I love Christie, Sayers and Allingham, but Marsh is the favorite of my heart. I’ve read some of her books so many times I almost know them verbatim. In all of her books, there are certain threads that hold constant, or that she dips back to. She was born in New Zealand, and her name, Ngaio, is a Maori word for a flowering tree. New Zealand often figures in her novels, as does a respect for the Native Maori culture.

The other two threads that run through her books are theater – a lifelong passion for Marsh, who also worked as a producer, and was instrumental in bringing travelling theater companies to New Zealand. She especially, and naturally, loved Shakespeare and specifically Macbeth. There are several of her novels nodding to the play – in Final Curtain (1947), her character Troy paints a past his glory actor as Macbeth; in Surfeit of Lampreys (1940), the character of Lady Macbeth serves as a clue; and in her final novel, Light Thickens (1982) she basically stages Macbeth as the major part of the plot.

The other two threads that run through her books are theater – a lifelong passion for Marsh, who also worked as a producer, and was instrumental in bringing travelling theater companies to New Zealand. She especially, and naturally, loved Shakespeare and specifically Macbeth. There are several of her novels nodding to the play – in Final Curtain (1947), her character Troy paints a past his glory actor as Macbeth; in Surfeit of Lampreys (1940), the character of Lady Macbeth serves as a clue; and in her final novel, Light Thickens (1982) she basically stages Macbeth as the major part of the plot.

She was also a painter, who exhibited her work with a Christchurch based group of artists between 1927-47. The artist thread runs through her work as well, as Alleyn’s eventual wife, Agatha Troy, is a well known painter. In Artists in Crime (1938), we get a look inside Troy’s studio; in Clutch of Constables (1968), Troy is on a river tour through Constables’ England. Of course, in both cases, a corpse intervenes.

Like Sayers’ Harriet Vane and Peter Wimsey, Agatha Troy (or Troy, as she’s generally known in the books) is reluctant to marry Alleyn, who is instantly smitten with her. They meet in Artists in Crime, and she agrees to marry him in Death in a White Tie (1938). Her reasoning is similar to Harriet Vane’s: she wants to be her own person, and she’s wary of Alleyn’s job though she’s often helpful to him, after they are married, as a sounding board. Their relationship, a happy one, is an unusual one I think for the time period, with both husband and wife having vital and notable careers. While I am always puzzled by Troy’s initial wariness to Alleyn, I also applaud her ability to stand up for what she feels is important.

Most if not all of Marsh’s books involve a complicated method of murder and/or solution. One of my favorites, Overture to Death (1939) has a devilishly complicated set up involving a gun concealed inside a piano. She’s also somewhat fond of beheadings – Death of a Fool (1956) and Light Thickens both see their victims beheaded, and in Surfeit of Lampreys the victim is impaled through the eye with a meat skewer.

While these various ladies – Christie, Sayers, Allingham and Marsh – are often credited with creating what are now known as cozies, I think they are actually far from cozy. Sayers began to deal with the aftermath of crime (Busman’s Honeymoon, 1937, as Wimsey laments his part in sending a man to the gallows), Christie’s body counts were often so high only one or two survivors are left at the end of the book (And Then There Were None, 1936, and Death Comes as the End, 1944) and she also wrote one of the earlier (and creepier) psychological suspense novels, Endless Night (1967). Allingham may perhaps fit the cozy moniker best with her eccentric characters of Campion and Lugg, but even she delivers a real psychological wollop in her masterpiece, Tiger in the Smoke (1952) where Campion is almost a sidebar character. I think the description that fits these writers better is traditional, as they mostly adhered to the format, now called traditional, of a detective who is smarter than everyone else, clues that are fairly laid, and the solution often involves collecting all the characters together in a final dramatic scene which reveals the killer.

All of these women, brilliant at working within this traditional structure, made it very much theirs through their ownership of specific characters and spectacular plots. Through a long career as a bookseller I was often asked what my favorite mystery was, and I was able to answer: Ngaio Marsh’s Surfeit of Lampreys, also known as Death of a Peer. A couple years ago a writer friend asked me this question, and I answered, mentioning I’d read it many times, and he was amazed I’d read any mystery more than once. When we read it in our book club, the club thought there were “too many” characters, but with both of these things, I take issue.

All of these women, brilliant at working within this traditional structure, made it very much theirs through their ownership of specific characters and spectacular plots. Through a long career as a bookseller I was often asked what my favorite mystery was, and I was able to answer: Ngaio Marsh’s Surfeit of Lampreys, also known as Death of a Peer. A couple years ago a writer friend asked me this question, and I answered, mentioning I’d read it many times, and he was amazed I’d read any mystery more than once. When we read it in our book club, the club thought there were “too many” characters, but with both of these things, I take issue.

For one, I am a fervid re-reader, and finding a book I love will re-read it, often at night before I fall asleep. And “too many” characters? I also disagree, and almost all of them are in the same family. For all I love Christie, Allingham and Sayers, they’ve never brought a tear to my eye. Marsh sometimes does, and she did in this novel, which centers on young Roberta Grey.

We meet her as a schoolgirl in New Zealand, where she attends school with the impossibly glamorous Frid Lamprey, who invites her home during a school break. Roberta is immediately smitten with the large Lamprey family: the unfocused but kind father, the sweet mother, the twin boys who are almost like one person, the oldest brother, Henry, who Roberta finds attractive, the emerging from babyhood Patch, and the youngest, Mike. Marsh sketches in a picture of the beautiful glory of New Zealand, and the casual, careless attitude of the Lamprey family toward money. They are somewhat in exile in New Zealand, but then a financial turn around sends them back to their beloved London.

This all happens in the prologue. When we next encounter Roberta, she is onboard ship heading for England after losing her parents. She’s looking forward to visiting the Lampreys before going to live with a kindly aunt, her last relative. What Marsh captures so well is Roberta’s youth and her first rapturous encounter with London, seen through the busy lens of the Lampreys. I always imagined it must be a reflection of Marsh’s own first encounter with London.

The Lampreys, when she encounters them at home, are in the throes of a typical financial crisis and are girding their loins to ask the uncle for a loan. This sets off a disaster involving the uncle being stabbed through the eye in the elevator. Inspector Alleyn is called in, along with his retinue which includes the faithful Inspector Fox. The mystery part of the novel is clever and as I mentioned is cracked by Alleyn utilizing Lady Macbeth’s character as a clue.

The book is full of the Lamprey family, and if you are annoyed by them – their casual spending of money they don’t have, their status, their enjoyment of each other, their family unity – you won’t enjoy the book, and I know there are readers who don’t like it for that reason. However, it has wonderful pace and movement and it is really alive. The parts when Roberta leaves the Lamprey’s apartment really give a quick, living picture of wartime London.

There are passages and descriptions in this book that I treasure, and look forward to every time I read it. I always find myself completely immersed in the Lamprey’s world, their problems, and in Alleyn’s skepticism about their charms. The solution to the crime is full of drama, and the Lampreys in possession of a fortune at the end oddly humorous. In short, this book has it all: humor, drama, three dimensional characters and setting and a fabulous story. As I often told customers when I sold them this book, it will make your life better.

Other wonderful Marsh titles:

Clutch of Constables, where Troy’s artistic journey on a river barge ends in murder but still finds Troy appreciating the gorgeous English landscape that inspired painter John Constable.

Hand in Glove (1962), a mid career effort involving a scavenger hunt at a country house party. The solution is incredibly tricky.

Night at the Vulcan (1951), which takes place in a single night in a slightly run down theater. The plot, because it takes place in such a tight time frame, has real urgency, but the writing in the opening chapter may be the best thing about the whole wonderful book.

Killer Dolphin (1966),director and playwright Peregrine Jay realizes a dream when a backer agrees to restore the old Dolphin theater; he creates a play around the backer’s discovery of a glove that may have belonged to Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet. A Macguffin if there ever was one!

Death of a Fool takes place in the deep English countryside and is an astounding look at an ancient winter solstice play, performed outdoors and in this novel, ending in a murder. Worth reading for the cultural education and dialect alone.