To my mind the most unjustly neglected mystery writers of all are the women who wrote non-series books around the middle of the twentieth century. Part of the neglect has to do with the fact that series fiction has come to dominate the genre, but a lot of it has to do with sheer sexism. Perhaps it’s no surprise that the hard-boiled guys who saw women as little more than leggy appendages and prized gun play, fisticuffs and rye whiskey overlooked or derided the housewife, widow or mousy poor relation protagonists of these books, but what is surprising is the treatment they would come to receive from their own sex. When the sixties and seventies rolled around female mystery heroines picked up guns and came out slugging, empowered by a revolutionary new world of economic and social possibilities. In an era of “I am woman, hear me roar,” their muzzled predecessors became an embarrassment, a page to be turned and forgotten rather than a legacy to be celebrated.

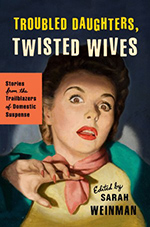

Which is nonsense, of course, as Sarah Weinman’s fantastic anthology Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives clearly demonstrates. Rather than being weak doormats, the women in these stories struggle furiously and ingeniously against the stifling constraints of their society, and the book is a delicious box of poisoned truffles, with delectable surfaces of suspense and murder surrounding the more bitter central truths about their lack of opportunity, their victimization and the tenuousness of their social position and very identity.

Which is nonsense, of course, as Sarah Weinman’s fantastic anthology Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives clearly demonstrates. Rather than being weak doormats, the women in these stories struggle furiously and ingeniously against the stifling constraints of their society, and the book is a delicious box of poisoned truffles, with delectable surfaces of suspense and murder surrounding the more bitter central truths about their lack of opportunity, their victimization and the tenuousness of their social position and very identity.

There are crackerjack stories by authors I’ve long championed, like Celia Fremlin, Dorothy B. Hughes, Helen Nielsen and Charlotte Armstrong, bestsellers in their time, but little remembered today, as well as some who are still somewhat better known like Shirley Jackson and Vera Caspary. There’s excellent work by writers I’ve never heard of who specialized in short stories, a genre that’s also underappreciated these days, which is a shame because it’s such an exacting skill, dependent on an economy somewhat forgotten in this era of eight hundred page door stoppers. There’s a very limited space in which to pull the threads of plot, character, setting, theme and everything else together, and even the best of these authors can leave a few loose ends dangling here and there, but when the thing is done right, as in my favorite story in the volume, Elizabeth Sanxay Holding’s “The Stranger in the Car,” the effect is concentrated and extraordinarily satisfying. Editor Weinman is to be lauded for digging through reams of old magazines to unearth these neglected treasures, which still shine brilliantly today. (Jamie)