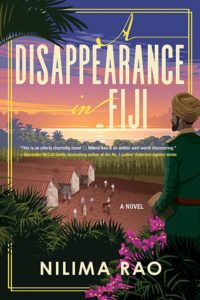

This book is such a fun read, which is odd as the subject matter is difficult. Set in 1914 Fiji, at the time a British colony, the rollback of slavery in Britain made it difficult for colonies to obtain workers for their sugar cane and other plantations. The solution (a fairly short lived one) was to import Indians as indentured servants. The workers signed up for a set time – five years – and then were free. Ultimately, about half returned to India; about half stayed in Fiji. That’s the setting.

This book is such a fun read, which is odd as the subject matter is difficult. Set in 1914 Fiji, at the time a British colony, the rollback of slavery in Britain made it difficult for colonies to obtain workers for their sugar cane and other plantations. The solution (a fairly short lived one) was to import Indians as indentured servants. The workers signed up for a set time – five years – and then were free. Ultimately, about half returned to India; about half stayed in Fiji. That’s the setting.

The main character is disgraced police Sergeant Akal Singh, who has been demoted from a sweet post in Hong Kong to the remote isle of Fiji. He’s on a no-win case – the “night prowler” – a guy who looks in windows at night. He’s only been seen by children, who all describe him differently. Singh is truly stuck in limbo, when a Catholic priest makes a stink about a missing “coolie” woman at a plantation owned by a powerful British couple.

“Coolie” was the derogatory term for an Indian worker. The plantation owner is insisting she’s run off with the overseer; the priest is insisting she would never have left her daughter behind. Singh is assigned this thankless case as well, told by his boss to solve the problem without creating political waves. After some investigating in town, Akal heads out with to the plantation with Robert, a doctor who tends to the workers, to see what’s actually going on.

The plantation owner will barely look at Singh, and when Robert insists the two men bunk together, they end up in the abandoned overseer’s house as the owner refuses to have an Indian in his home. While this book is set in a different time and place, the racism seems to be the same. Robert’s genuine concern and care for the workers gives Singh an in to meet some of them.

This sounds so grim, doesn’t it? Somehow, it’s not. The story is fast paced, and the unravelling of the missing woman’s life is fascinating. The characters of both Akal and Robert are so charming and appealing that they carry the novel in their capable hands. You’re rooting for Singh to overcome whatever disgrace expelled him from Hong Kong (a disgrace revealed in the course of the novel), and the setting is evocatively written. You can feel the warmth of the jungle. Most moving to me was Singh moving through the coolie “lines” (or housing) at dinner time, with the cooking smells bringing him back home to the Punjab.

The layers of Colonial society are well dissected by the author, and the light she brings to the living conditions of the workers (especially the women) is harsh. As you might expect, the life of an indentured servant on a plantation was not pleasant. Singh is fighting an uphill battle as he struggles to get a hearing for this missing woman, someone basically dismissed by the British colonials as unimportant. To her daughter, the missing woman is not unimportant. She’s her mother. These elemental ties of emotional truth make this novel a powerful as well as an engaging read and a wonderful debut. — Robin Agnew