She knew that something was happening in the house.

She knew that something was happening in the house.

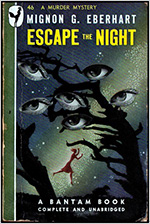

To me that line, the first one from 1944’s Escape the Night, is probably the ultimate Mignon Eberhart sentence. Eberhart, little remembered today, was once called “America’s Agatha Christie,” and wrote almost sixty novels, the first published in 1929 and the last in 1988 when she herself was 88.

On one of my buying trips to the local library bookshop I came across a nice uniform set of about ten of her titles, bought a couple of titles I knew I hadn’t read (Robin’s voice in my head admonishing we have ENOUGH books) but remained haunted by the others, ending up browbeating a kindly old lady into selling me the rest before the shop opened the next day. And excepting the browbeating stuff, I am very glad I did, because these are the perfect books for the snowy, cold, fluctuating fluey winter we’ve all been suffering through. I’ve been savoring them one by one like that box of Christmas truffles that didn’t last half as long.

The ones I’ve read were written at a brisk clip from the early forties to the early fifties and are all stand-alones, but share common themes and elements, giving both a suspenseful unpredictability and a comforting familiarity.

First of all, there’s the house, usually a big and old, like the gothic ones in Rebecca or Jane Eyre, familiar to the protagonist yet filled with creaks, secrets and strange things hiding in strange places.

In that house are the long time owners, a family, their dependents and their childhood circle of friends, friends familiar enough to seem, for better or for worse, like family. Most importantly there is a man and a woman, who know they love each other, but can’t get comfortably together because of circumstances and various complications, the crucial complication being, of course, murder.

Murder had walked in that house and the house remembered it.

Murder had walked in that house and the house remembered it.

[Another Woman’s House, 1947]

She was murdered about twilight with the shadows of fog and coming night blurring trees and shrubbery together in an amorphous mass that seemed to advance and watch and then retreat, like unwilling witnesses who would not come forward.

[Hunt With the Hounds, 1950]

Because her protagonists aren’t hard boiled private detectives or nosy old ladies who habitually trip over corpses, Eberhart can express the panic of regular people whose lives are upended by crime.

It took a while to get a fact like murder into one’s mind. It took a while to drag one’s self out of that dreadful pit of confusion and darkness and horror.

[Escape the Night, 1944]

Naturally, things are more horrible when the victim is someone close to you, and even more horrible when the killer may well be, too. The worst part of all is that the killer is probably still in the house with you.

But there were not many other people who knew her well enough to hate her. Murder implies a certain intimacy. Hatred implies a dreadful fellowship.

[House of Storm, 1949]

And that’s another thing that strikes me about Eberhart’s work — the intimacy of it, the domesticity. It’s an interior world, one where breaks in the case come not from some tough guy shuttling around to punch a mug in the kisser, but from the small, feminine things that few men even notice: a new bracelet, an old scarf or a strangely familiar “small locket in black enamel and pearls.” The tension comes from people standing in the drawing room trying to carry on with the formalities amid the ultimate uncivilized act, questioning or accusing glances and veiled insinuations striking with as much force as bullets. Her plots remain crackerjack, her observations acute.

It’s impossible to picture now how huge and unquestioned Eberhart’s stature was from her first book until the time she died. Maybe it’s the fact that her usual milieu was the haunts of the upper class makes her seem less authentic to contemporary tastemakers, but few have heard of her and even fewer have read her. She even remains invisible to those dedicated to rediscovering midcentury women authors, who find the bald misanthropy of Patricia Highsmith and the like far more pertinent to our present Gone Girl line-up of damaged, unreliable and violent anti-heroines. But, as Nancy Drew proves, there will always be a place for a plucky, honest female who finds herself in the midst of mayhem.

When Dorothy Hughes was named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America, Eberhart wrote these words, which certainly apply to herself as well:

I appreciate the fact that Mrs. Hughes introduces characters who spring from the framework of a specific story, ones who act intentionally or even unintentionally to discover and prove the guilt of the murderer (and this is very important: we don’t just assume guilt — we have been presented with enough evidence to sway a jury).

Hughes in her turn, writing of Eberhart, who’d been made the second female Grand Master (Agatha Christie being the first) seven years earlier:

A Mignon Eberhart novel, without need of a mystery plot, would stand on its own, a mirror of the modes and manners of the twentieth century.

A simple, subtle sentence from Another Woman’s House illustrates the point perfectly:

She peeled her stockings with, since the war, habitually careful hands.

(Jamie)