There’s something about decapitation that has a primal effect, abhorrent yet inescapably fascinating, possessing an atavistic kick. Although removing a fellow human’s head and displaying it as an object is an act, like cannibalism and incest, that most of us would prefer not to think about, anthropology testifies that there are certainly contemporary tribes of “head-hunters” or even “head-shrinkers,” who still indulge in such behavior, and it’s disingenuous to believe that our ancestors didn’t take part in similar ritual activity.

There’s something about decapitation that has a primal effect, abhorrent yet inescapably fascinating, possessing an atavistic kick. Although removing a fellow human’s head and displaying it as an object is an act, like cannibalism and incest, that most of us would prefer not to think about, anthropology testifies that there are certainly contemporary tribes of “head-hunters” or even “head-shrinkers,” who still indulge in such behavior, and it’s disingenuous to believe that our ancestors didn’t take part in similar ritual activity.

After all, it wasn’t that long ago that severed heads were displayed on the gates of London as a symbol of royal power, and various radical groups still prefer beheading as a method of dispatching their enemies, presumably for its awful, awe inspiring qualities. Even the guillotine, which was developed in a rigidly scientific way as the most humane and efficient

method of execution today stands as a universal symbol for bloody terror.

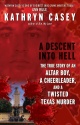

Which (perhaps belatedly) brings me to the subject of this essay, the excellent Kathryn Casey true crime book A Descent into Hell: the True Story of an Altar Boy, a Cheerleader, and a Twisted Texas Murder. Despite Casey’s formidable authorial skills, the book would be pretty run of the mill had former altar boy Colton Pitonyak been content to merely shoot and kill former cheerleader Jennifer Cave. It’s the “twisted” part that’s the grabber, producing the inevitable frisson that makes the book stand out. What contemporary novel can match this passage in which the victim’s step-father makes a discovery almost beyond comprehension:

When Jim looked down at the bathroom floor, he saw a large trash bag. Without looking inside, he knew what it held. Someone had cut off Jennifer’s head.

Or how about this excerpt, bone chilling in its very ordinariness:

Jennifer’s head was removed and set on the autopsy table beside her body. She still wore her earrings and her makeup, and, except for stab wounds across the side of her face, she looked remarkably like her Texas driver’s licence photo.

The inevitable question becomes — what kind of person would do such a thing? This is where Casey excels, because, as I have said before, True Crime, like any branch of literature, is dependent on character.

At first glance Colton’s descent into murder and dismemberment seems inexplicable. His former teachers and jock buddies describe him as an absolutely exemplary person, brilliant and athletic, the ideal student and model young gentleman of privilege. Casey, however, exposes him as a figure familiar to any High School outsider, the two faced phoney who is able to show authority the mask they want to see while morphing into a sadistic bully the moment their attention is diverted. Eddie Haskell, anyone?

Of course his parents and faculty fans don’t want to admit they were hoodwinked and blame Colton’s downfall on that contemporary boogie man, drugs, and it’s to Casey’s further credit that she resists this facile explanation. Crystal Meth is indeed nasty, nasty stuff, the allure of which has always eluded me, but no drug can bring out something that’s not already there. Take the victim Jennifer Cave for instance, the product of a disordered childhood and a broken home, whose attraction to drugs is cogently explained:

More than a decade earlier, Jennifer had been a little girl in love with The Wizard of Oz. Perhaps the drugs transported her to an Oz of sorts, much as the tornado had Dorothy. With the drugs, her nagging self-doubts were calmed, the world was more beautiful, there was nothing to fear, no one to disappoint, no future to fret over, only the immediate moment to enjoy.

Still, even as she became a drug user, Jennifer retained her essentially positive nature, even to the extent of wanting to redeem a needy, manipulative lost soul like Colton, for whom drugs had merely enhanced his vicious, predatory instincts. Even in the depths of addiction, however, he still retained the ability to soft soap authority, essentially skating on drunk driving and possession charges.

There is even a third memorable character in A Descent into Hell, one Laura Hall, Colton’s satanic soul sister, obliging consort to the alpha male, assistant to the dismemberment and traveling companion on the abortive flight to Mexico. Even early in life Laura seemed arrogantly foreign to normal human feelings. Interesting, both Laura and Colton’s parents in testifying for leniency in the punishment phase of the trials insist that their children were “gifted athletes,” as if that fact was in itself evidence of good character.

But the question remains WHY. In the grip of a methed-up pipe dream informed by Scarface and The Godfather we can speculate that Colton and Laura intended to disguise the identity of the victim. But in today’s CSI world, can they really have believed this was possible, especially when that victim was known to be a missing person actively sought by her family?

And then there’s the grim details of the deed, suggesting a warped levity undreamt of by even the deadpan miscreants of Goodfellas:

After the bullet to Jennifer’s aorta killed her, someone cut off her head. Then a gun was fired upward, into her head through the severed neck.

Along with the dozens of cuts to the body, it now appeared even more certain that someone had defiled Jennifer’s dead body for no other reason than amusement.

It doesn’t take a huge leap of the imagination to see the scene in that apartment, framed in blood splatters and drug haze, as a return to some primal, savage condition of humanity, partaking of a taboo mystery not unlike that known by an Aztec priest as he drew out a still beating heart. But as abhorrent as that priest’s act was, at least it was informed by a dense, mystical cosmology, whereas Colton and Laura only had DVD’s and gangsta rap to guide them in their ultimately pathetic efforts. In the end Laura’s own explanation is as good as any:

“Think of it,” Hall said dreamily. “How many grandmothers can tell their grandchildren that they cut up a body.”

Unless written by Truman Capote or Norman Mailer, True Crime is considered a debased, pulp genre, one that can safely be snickered at by every Middlebrow. But I challenge anyone to produce a book that shocks the reader’s complacency, shines a harsher light on modern society or raises the question of what it means to be human in a more profound way than A Descent into Hell. (Jamie)