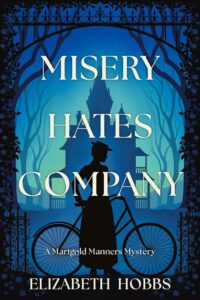

Series debut

I really, really appreciate a book that’s able to keep me guessing. This novel, while adhering to many of the expectations applying to cozy historicals, also completely upends them in other ways, to the point that even when I was about three quarters of the way through I was still not quite sure where the story was headed. (I was more than eager to discover where that might be, however.) As the book opens in 1890’s Boston, Marigold Manners has just lost both parents to the flu pandemic. And worse, she’s discovered that they died broke. While Marigold had formerly been a firm part of upper crust Boston, it appears now as though she will have to leave ritzy Wellesley College, abandon her dreams of archaeology, and throw herself at the mercy of her relatives. She has a last, final night out with her friend Isabelle and her devoted society hunk, Cab. So far, so standard.

I really, really appreciate a book that’s able to keep me guessing. This novel, while adhering to many of the expectations applying to cozy historicals, also completely upends them in other ways, to the point that even when I was about three quarters of the way through I was still not quite sure where the story was headed. (I was more than eager to discover where that might be, however.) As the book opens in 1890’s Boston, Marigold Manners has just lost both parents to the flu pandemic. And worse, she’s discovered that they died broke. While Marigold had formerly been a firm part of upper crust Boston, it appears now as though she will have to leave ritzy Wellesley College, abandon her dreams of archaeology, and throw herself at the mercy of her relatives. She has a last, final night out with her friend Isabelle and her devoted society hunk, Cab. So far, so standard.

Of all the letters from far flung cousins and aunts the one Marigold chooses to accept is from her cousin Mrs. Sophronia Hatchett, who lives on a place called Misery Island, off the New England shore. Marigold has never heard of Sophronia, but she’s intrigued by her letter, which promises to reveal secrets and right family wrongs. And from then on, things take a turn to the weird and uncanny. It reminded me a good bit of one of my favorite girlhood books, Joan Aiken’s Nightbirds on Nantucket, and heroine Dido Twite’s stay with her Aunt Tribulation. Misery Island is all the reader might expect from the name, and the well dressed Marigold arrives at the train station with her trunks to find no one there to meet her. What she does find, after some asking around, is a drunk on the beach with a little boat who rows her over to the island (and she has to assist him).

The island is desolate, her relatives, rather than being welcoming, are scattered around the island and often downright hostile when they do happen to encounter her. Cousin Sophronia is cryptic beyond belief, and the only food to hand is the goopy stew made by Cleon, the inebriated rower. Marigold, not one to let things lie or to wallow in misfortune, rolls up her sleeves the next morning and gets to work cleaning the kitchen. She also makes her way across the water to town, where she finds the library, retrieves her bicycle (a real novelty in the 1890s) and forms a women’s bicycle club. She’s truly the model of an independent female, or “new woman,” and, as such, finds very little fellow feeling with her new cousins.

She then determines to disarm them with charm – learning that her lovely cousin Daisy has a secret beau, cousin Saviah has a talent for singing, and cousin Wilbert intends to raise sheep on the desolate island. She finds their father, Ellery, intimidating, as every time he sees her he starts ranting and shouting. Her putative patron Sophronia remains aloof, and, to add to her dread, Marigold is almost certain on her initial voyage across that she’d seen the body of a young woman under the water. This body remains submerged in the plot, not resurfacing again until later on in the novel.

The middle bit has a bit of a Cinderella feel as she helps her cousins begin to realize their goals, meanwhile reuniting with Cab at an actual ball, ballgowns supplied by couturier friend Isabelle. She also befriends Lucy, a young black woman who cooks meals and leaves them on a tray outside the door of matriarch, Alva, who never leaves her room.

That gets us through about three quarters of the book, in turns a story of identity (Marigold’s), a dysfunctional family, adventure, and a gothic, haunted house. After that it morphs into a straight up mystery when one of the family is discovered murdered and Marigold and Cab have to be the ones to solve it in the face of a local constable who seems totally unsuited for the job of detection. This was a charming, funny, and at times bleak story which has a surprisingly happy ending and a wonderful central character. Marigold is a blooming heroine I can only hope to encounter again. — Robin Agnew