Classic

Publication date: 1963

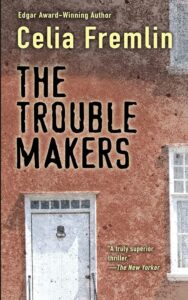

Of all the mystery variations, “Domestic Suspense,” like many things domestic, is the most undervalued, considered practically disposable. Regardless of their excellence or popularity, writers of the past who didn’t write detective series are seldom remembered or celebrated today. One of my favorites, Celia Fremlin, who the New York Times of the time quite aptly called a mistress of insight and suspense, is fortunately not completely lost. Dover Books, sovereign of the uncopyrighted, has three of her titles in print and I had the pleasure of writing an entry about one of them, The Hours Before Dawn in the epochal Crum Creek classic 100 Favorite Mysteries of the Century.

Of all the mystery variations, “Domestic Suspense,” like many things domestic, is the most undervalued, considered practically disposable. Regardless of their excellence or popularity, writers of the past who didn’t write detective series are seldom remembered or celebrated today. One of my favorites, Celia Fremlin, who the New York Times of the time quite aptly called a mistress of insight and suspense, is fortunately not completely lost. Dover Books, sovereign of the uncopyrighted, has three of her titles in print and I had the pleasure of writing an entry about one of them, The Hours Before Dawn in the epochal Crum Creek classic 100 Favorite Mysteries of the Century.

That book was set during the sleep deprivation of a young wife and the temporary insanity caused by the arrival of a newborn. In the midst of it all, a new mother finds that her very real fears about a possible murderer in the house can only too casually dismissed as hysteria.

The Trouble Makers is similar, but at a later stage of a woman’s life, a slower burn set amongst the push and pull of a household with three small children and not enough money

Because the more leisure you gave to one person, the more you are automatically taking away from someone else; it all cancels out somewhere, and that’s why life never gets any easier, no matter what is invented.

In the early 60s the world was changing, but the social expectations, particularly around women, remained constant. Gone were the days when even the smallest household with pretensions could take advantage of a large pool of available servants. Heroine Katharine must take a part-time job to support their young family, yet is also expected to completely, effortlessly and efficiently manage the household, including food, childcare and cleaning, all economically in service of a mythical Edwardian ideal tartly upheld by her husband. The wives are all united in their hatred of similarly unreasonable hubbies, while still waging passive aggressive tiffs over their hypervigilantly observed patches of status. Crowded together in this still austere London, living across the fence from one another, they are forever self-consciously observing and being observed.

A lovely anti-husband natter was in progress, and Katherine felt herself drawn to the sound like an alcoholic by the clink of glasses.

Other people’s troubles were like nourishment to her – something concentrated and quick acting out of a jar.

Into this claustrophobic world comes an actual life or death event – one of the husbands is stabbed. His wife, Mary, confides the identity of the culprit to Katharine, and she watches horrified as instead of the truth, an enormous face saving lie spreads across the neighborhood. At first she resists, but eventually decides it’s all for the best and acquiesces, even urging Mary to insist on the lie. In a brilliant and shattering denouement, Fremlin suggests that it is the pressure of this false consensus itself that causes the falsity to take menacing human form.

Like another suspense maven of her time, Margaret Millar, Fremlin suffers slightly from the pat psychology the era, but as the Times said Fremlin excels in both insight and suspense, and the best parts of this book are the subtly boiling plot and the mordant observations of Fremlin’s creation Katharine.

This feeling that they were fellow-sufferers of each other – that they were painfully evolving the same hopeless techniques for dealing with unwelcome emotions – moved Katharine strangely.

Despite the rancor, Fremlin suggests that there may yet be a way forward for society and even husbands and wives – if only her protagonist can survive. — Jamie Agnew