Many thanks to author Bella Ellis for this fascinating essay. Think you have nothing in common with the Brontës? Read on…and check out Ellis’ latest novel, The Vanished Bride.

Many thanks to author Bella Ellis for this fascinating essay. Think you have nothing in common with the Brontës? Read on…and check out Ellis’ latest novel, The Vanished Bride.

Until recently, if you lived in a first world country, you will have become used to living a low risk life. Not one that is totally danger free, but one where you didn’t have an imminent sense of peril when you left your house, particularly in terms of your health. In fact, in recent decades for those of us lucky to lead a relatively privileged life, it’s easy to completely ignore our own mortality without very much effort. What we forgot is that that sense of security is a relatively recent development, and as the emergence of COVID-19 has proven, its one that can still be quickly swept away. We don’t have to look very far back in time to see an age when people lived and died amongst a host of deadly diseases and had to learn to accept the risk. Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë are shining examples of what can be achieved when life is limited by circumstance. So, what inspiration can we take from them as we navigate our way through this global pandemic?

In mid-nineteenth century Haworth, the danger of falling ill to a potentially fatal disease was a fact of life. Victorian knowledge on how diseases spread meant there were no lock downs, no face masks and no treatments for endemic infections such as Tuberculosis, Typhoid and Cholera. And public health measures like clean drinking water, drainage and underground sewers wouldn’t come into effect until later in the 1800s. As a consequence, a lot of people died very young from disease. In fact, in 1845, the year when all the Brontë children reconvened under one roof again after years of working or studying away from home, the average life expectancy was just 25 years old, worse than even the most notorious London slums.

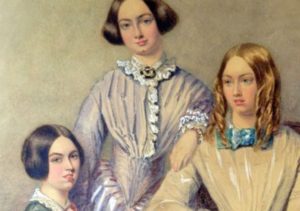

Victorians of all classes expected to die, and they expected to die young. If a woman became pregnant, she knew her life was in danger and if she survived the birth, she knew the chances of losing her child in the first five years of its life were very high. Health and longevity were considered blessings, not entitlements. Risk was so tied up with the business of living that it wasn’t considered at all. Knowing the prevalence of disease, people went on with their work, with love, with creating families and, in the case of Charlotte, Emily and Anne, writing wonderful, ground-breaking novels, each one filled with a passionate lust for life.

Not because they were braver or more stoic than contemporary humans (though I suspect they were), but because they had no choice. In the face of almost impossible odds, these were three women who battled hard to live life as meaningfully and impactfully as possible in a world that was largely blind to the creative talents of any woman, let alone lower middle-class spinsters. Life dealt them more than their fair share of blows that might devastate the best of us, but in each case these women went on, without giving in to grief, fear or heartbreak. They show us incredibly strength through their resilience and determination to live whatever life may be afforded them as well as they possible could, not only for themselves and each other, but for the good of all.

We often think of Haworth as a tiny hamlet on the edge of the moor, but in 1845 it was very much a working village, desperately trying to keep up with innovation. The industrial revolution was in full swing, which meant that the traditional employment of weaving was under threat by mass production and more and more of the population was being forced to work in the mills that were springing up everywhere. The moorland was also intensively farmed for peat, crops and livestock. The village was over crowded, with an average of one ‘privy’ (toilet) shared between 24 households. People often used the streets to relieve themselves and the main water supply to the village was right next door to the cess pit which frequently overflowed. Add to this the town’s graveyard, famously situated within sight of the Brontë Parsonage. Today it is a beautiful, haunting place full of nature and history. But in 1845 it’s estimated that it held around 44,000 bodies on a tiny plot. Graves were often occupied by up to ten inhabitants. This in itself might not have been a problem except for a series of factors unique to Haworth. At that time, it was common practise not to mark graves with standing headstones, but with flat ‘table top’ markers, which prevented moisture rising from the ground. This was a problem because the main water supply for the village flowed down off the moors and into the town well, after filtering through the graveyard. In short, the drinking supply was constantly contaminated with corpse slurry. The Brontë family probably only survived as long as they did because they had not only their own privy, but also their own well. When I think of these young women, working and writing, and hoping and dreaming in this deadly environment, I am reminded of the power of imagination.

Creativity and the creative industries are often the first to suffer in an economic decline, but it is the very means of escape through story, cinema and art that we all need to survive and stay sane when life is particularly stressful.

Creativity and the creative industries are often the first to suffer in an economic decline, but it is the very means of escape through story, cinema and art that we all need to survive and stay sane when life is particularly stressful. Surrounded by all this constant worry, and living so close to tragedy and poverty, Charlotte, Emily and Anne managed to channel everything they knew into fantastical worlds and brilliant novels. It’s is probably no coincidence that after losing their mother and two sisters when they were still small, they took refuge in creating their own imaginary worlds of Gondal and Angria, worlds that might be thought of as early examples of fantasy fiction and fan fiction. As they grew up, using, feeding and living at least partly in their imaginations enabled them to create ground breaking works of fiction that are still just as compelling and relevant today as they were a hundred and fifty years ago. They show us our creative and imaginative lives are not only important during times of duress, but necessary. In these difficult times, we can find not only comfort, but power, within our own minds.

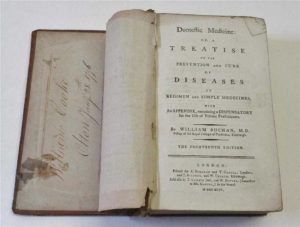

Just as death was a constant companion to every Victorian, health was a constant concern. We only have to take a look at Patrick Brontë’s much used 1826 edition of Modern Domestic Medicine which he not only referred to often, but also annotated with any information he felt was more up-to-date and useful. Keeping his family well was crucial to Patrick, not least because he lost his beloved wife to what was probably ovarian cancer, but also his two daughters, Elizabeth and Mariah, contracted TB at Cowan Bridge School, both dying before the age of ten. It’s heart-breaking to know that despite his best efforts, Patrick would lose his entire family decades before his own health declined.

Seeking out understanding, consulting experts and following the best available advice was as key to the Victorians as it is to us today. The Brontës knew only too well what the consequences of making bad decisions could be. Patrick was a constant campaigner for health and living standards reform, and a great believer in the progress that was being made by science and medicine. In 1846, nearly blind, Charlotte accompanied him to Manchester where he underwent cataract surgery, without anaesthetic, on both of his eyes. It was a new and untested treatment, but it succeeded in restoring much of Patrick’s sight – not to mention that Charlotte began working on Jane Eyre while her father was recuperating. A man of God, and a man of faith, Patrick saw scientific advancement as part of God’s work, not an opposing force to it. He did his best to protect his children, but was unable to save Branwell from his addiction to alcohol and opiates, and he couldn’t prevent Emily and Anne from succumbing to tuberculosis. And when Charlotte died during the first trimester of her pregnancy, he must have wished that medicine had been advanced enough to save her.

If the Brontës had known then what we know today about basic hygiene and face masks as tools against the spread of COVID-19, you can bet they would have used them. They would have done anything to ward off the threat of potentially fatal sickness. Imagine if they had known that a simple face covering might have stopped Emily from picking up TB at Branwell’s funeral. Imagine if because she socially distanced, Emily had not passed on the disease to Anne. Imagine what amazing works of fiction and feats of living we might have benefited from then.

Today, we are all living with much more risk than we are used to, but we are not powerless. We can learn from the past to improve the future. We can learn to be stronger, more creative and above all to use the knowledge we have to protect ourselves and each other, so we can all go on to benefit from years of life that the Brontë sisters didn’t have.

Bella Ellis is the Brontë-esque pseudonym of an acclaimed author of numerous novels for adults and children. She first visited the former home of the Brontë sisters when she was ten years old. From the moment she stepped over the threshold she was hooked, and she embarked on a lifelong love affair with Charlotte, Emily, and Anne; their life; their literature; and their remarkable legacy. Her novel, The Vanished Bride, came out in paperback in July. Visit our store page to order a copy.