Q: First of all, what led you to add mysteries to your list of literary accomplishments? William Gibson has also moved from speculative fiction into the contemporary thriller. Do you see some kind of a trend?

Q: First of all, what led you to add mysteries to your list of literary accomplishments? William Gibson has also moved from speculative fiction into the contemporary thriller. Do you see some kind of a trend?

A: I don’t know that it’s a trend; maybe more a kind of artistic serendipity. Several people have told me that Available Dark reminds them of Gibson’s recent work, which surprised me — I admire Gibson immensely but didn’t really see any similarities until they were pointed out. I guess perhaps we share an apocalyptic view of The Way We Live Now, and a perception of 21st century cities as bell jars for global culture.

I’ve never hewn very close to the straight and narrow as far as speculative fiction goes. I have a low boredom threshold, and I get restless writing within a single genre, something which has probably cost me in commercial terms as publishers want you to stick with one thing to gain traction within a market. Believe it or not, Generation Loss actually started out as a contemporary fantasy novel called Crossing the Dream Meridian. I got a hundred or so pages of that written, and it just wasn’t working. I tried reconfiguring it as a straightforward horror novel. That didn’t work either.

I’m not sure how it was that I decided to recast it as noir, but I’ve always loved noir film and some of my favorite novels are contemporary noir novels — Kem Nunn’s Tapping the Source, Peter Hoeg’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow, Kerstin Ekman’s Blackwater. For a long time I’d had it in the back of my head that I’d like to attempt a psychological thriller — when I first saw Silence of the Lambs I thought, Hmm, now that’s something I could do. So I kept all the basic elements of Dream Meridian — the characters, the remote Maine setting, the protagonist from away who’s stuck on an island — and rewrote it as noir.

Obscure fun fact: one template for both Dream Meridian and Generation Loss is Michael Powell’s classic film “I Know Where I’m Going.” I threw Powell’s “Peeping Tom” into the mix and bam — there was Cass Neary.

Q: Another trend is mysteries set in northern latitudes. Both of your Cass Neary books climax in very cold places. What draws you to them?

A: Since childhood I’ve had a lifelong love of what W.H. Auden and C.S. Lewis term “northernness,” that brooding sense of mystery and adventure and threat that you get from the cold remote desolate places on the Earth. I’ve still never read Stieg Larsson’s books or seen any of their film adaptations. I’d never even heard of him till after Generation Loss was published and people told me it reminded them of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (nearly everyone said they preferred GenLoss: no lectures on the Swedish economic system!).

But as a kid I love the Icelandic sagas and Norse myth, and many of the earliest stories I wrote when I was eight or ten years old were dark, set in the north woods, or secondary worlds that resembled them. I’m just drawn to something in those landscapes — I find them incredibly beautiful yet also sinister. I have a friend who owns an island downeast, and the first time I visited it, more than a decade ago, I knew I’d set a novel there. I had the same feeling when I first visited Finland and Iceland. Both places remind me of Maine in a lot of ways — gorgeous countryside; self-sufficient economies that once relied on fishing and farming and now rely heavily on tourism; killingly long dark winters where people self-medicate with alcohol. Iceland’s tragic economic meltdown was like Maine’s collapse on a much larger and catastrophic scale. I visited Iceland both before and after the collapse, and I was so distressed and enraged by what happened there — I wanted someone to pay for the havoc wrought on an entire country by a handful of greedy people. That was the genesis of Available Dark.

Q: What were your influences from the mystery world? What mystery writers do you enjoy most?

A: Well, the writers I mentioned above — I’ve probably read Tapping the Source about ten times. (My 22-year-old daughter got a Tapping the Source tattoo after reading the book, and so did her father — I’d turned him on to it when it was first published.) I’ve read Smilla’s Sense of Snow several times — such a beautiful book. Same with Blackwater. I love Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley novels — I’m pretty much a sucker for sociopaths. I like Yrsa Sigurdadottir — I’m reading her new novel and it’s great — and Arnaldur Indridason. Henning Mankell, Kate Atkinson, Ian Rankin, Louise Welch, Tess Gerritsen, Paul Doiron. Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine, David Peace.

For whatever reason, I’ve always been drawn to European writers. They’re writing is often more fatalistic and less reliant on the great American trope of redemption. Atkinson is fantastic — I love how she just cuts her characters loose and follows them. I liked Peace’s Red Riding books — no happy endings there!

Q: Cass Neary is such an intriguing character. How much of her comes from your life?

I knew the early NYC and DC punk scenes well — I skated on the edge for some years, but was very fortunate never to fall through. I’ve often said that Cass is me if I’d had my moral and emotional brakelines cut in 1979 and gone off a cliff. I didn’t, but it’s easy and kind of cathartic for me to channel all that dark energy. I know about photography from working at the Smithsonian in the 1970s-1980s, when I spent a lot of time (much of it off the clock) in a darkroom. I’m a music geek, so I loved feeding all that rock and roll and black metal stuff into the books.

And Cass’s wiseass sensibility is definitely mine. Everyone in my family shares a macabre sense of humor — Hand family gatherings inevitably end with us around the dining room table, sharing stories of cannibalism and shark attacks.

Q: In Generation Loss Cass deals with the sixties generation and in Available Dark it’s the post-punk black metal crowd. What’s next for her?

A: In Flash Burn I’m sending her to London, where she’ll touch down amidst riots and general chaos. Over the last sixteen years, I’ve gotten to know North London pretty well, especially Camden Town, which is where Amy Winehouse lived and sang before her tragic death last year. So I’m going to have a character who’s a bit of an homage to Winehouse, along with another who’s a tip of the top hat to the late great flaneur Sebastan Horsley. Think 70s glam rock survivors and 21st c techno/house/ambient/electronic/etc. CCTVs are omnipresent in London, so writing murders that aren’t captured on video is a challenge, but a cool one. I spend all my time there looking for places that aren’t monitored by CCTV.

Q: There always seems to be a tension in mystery books between the demands of a self-contained novel and an installment in a series. How do you achieve a balance between the two and do you find a different dynamic in mystery and fantasy?

A: Most of my earlier novels are stand-alone works, except for the first three SF books — I found I didn’t have a knack for, or the interest in, sustaining a SF series. I do have a few characters, like Balthazar Warnick, who show up in different works as cameos.

Mystery as a genre seems to be more character-driven — you can have an Inspector Poirot, a Maigret, a Rebus or Tom Ripley, set them down wherever you want and basically see where they go. In Cass’s case, you get to see where she goes off the rails. She’s a classic outsider with a specialized gift — her ability to assess photographs and to recognize genius in certain artistic works — and her loner status, in a perverse way, gives her access to worlds she might not normally be able to enter, like those inhabited by art collectors. She moves in that shadowy interzone inhabited by drug users, drug dealers and various types of artists, and that’s a floating world — anywhere you go in the world, you’re going to find those people.

So I feel (I hope) that will keep both her and me on our toes — the fact that she’s got to be constantly on the move, like a shark.

I have two more Cass Neary novels firmly in mind, Flash Burn and a book tentatively titled Negative Space. Each is progressively darker than the one before. After that we’ll see.

Q: Esoteric rituals and the return of the pagan are recurring themes in your work. Would you say you’re more apprehensive or fascinated at the prospect of the archaic breaking out in the contemporary world?

A: I’m fascinated by it. I don’t believe that eldritch gods or the like are ever going to actually appear (any more than I believe in the Rapture), but I’m intrigued by people who do. As a lapsed Catholic, I’m fascinated by the notion of belief: how and why do people continue to believe in something despite any evidence to the contrary?

In the case of pagan and archaic belief systems, I’m even more intrigued — in many cases we have physical evidence of their beliefs, artifacts and the like, but no written record. So how do you recreate what those people actually believed in? Their worlds and thought systems would probably be utterly alien to us. I love the challenge of attempting to imagine how someone from such a different culture would think and breathe. I got my undergraduate degree in cultural anthropology, and my favorite part of my studies was working as a participant observer in the field, embedding myself in a group then doing ethnographic interviews and analyzing the results. It was a great experience for becoming a novelist.

Q: Your next book is classified as a young adult novel, but so was Illyria which was equally suitable for not so young adults. tell us about Radiant Days.

A: Illyria was originally written and published as an adult novel in the UK, so Radiant Days is my first full-length effort at a YA novel. There was a long learning curve. I had trouble getting the voice down, and at my editor’s suggestion I made Merle, the contemporary protagonist, eighteen years old. Which is roughly the same age as various characters in my adult novels.

Arthur Rimbaud, the other protagonist, was a challenge — how do you write a novel about someone who’s a bona fide genius, one of the greatest and most influential poets of all time, not to mention someone whose personal and artistic history has been covered by many far more experienced writers than myself? Despite reading everything I could in both English and French, I’m not a Rimbaud scholar; I wanted to write a novel that young people would read, while exposing them to the work of someone who reached his creative peak at nineteen, and wrote some of his most famous work while only sixteen or seventeen.

So I have Arthur and Merle meet up in 1978, when Merle is a brilliant but troubled graffiti artist living on the streets (think of a lesbian Basquiat). Their cross-time encounter is engineered by a mysterious and iconic guitarist who is himself homeless, and loosely inspired by the late Bob Stinson of the Replacements. Which makes this one of the very few novels to feature avatars of Rimbaud, Basquiat AND the Replacements.

Think of it as “Before Sunrise,” with a time-traveling Arthur Rimbaud and a contemporary lesbian graffiti artist wandering the streets of DC and Paris.

Q: As a contemporary of yours, another thing I really enjoy about your work is that i get all the cultural references. Do you feel, as I do, that our “blank generation” has gotten shortchanged in popular culture?

A: That is a GREAT question. That was the impetus for Generation Loss — I looked around and realized that my generation had somehow become this lost generation. We suffered so many losses over the decades — first drugs and alcohol, then the ravages of the AIDS epidemic. And the lifestyle choices of people who came of age at that time cast a long shadow over their later lives — speed and cocaine can cause longterm heart damage, among other things.

I felt that no one was telling their story. Punk was co-opted by the media and mass culture, as every youth movement is, though it’s actually had a longer shelf life than some, and a wider influence. You can draw a through-line from the black-clad beats to the punks to the Goths and on through black metal and every permutation of disaffected youth for the last forty years.

But so many of the people who were alive in that first wave of the early to mid-1970s and early 1980s are dead now; musicians and artists and writers and fans. I’ve lost many friends, some recently. They lived hard and a lot of them died hard, in some cases on the streets where they’d ended up. They were a lost generation: they were my generation.

It gave a real urgency to my writing Cass’s story. I felt that I wanted to bear witness to that time without romanticizing it, but still recognizing that there was a genuine dark beauty not just in the work created then but in the lives led and even the original nihilistic, nothing-to-lose impetus and aesthetic that fueled those lives — mine included.

Q: I love the story about how your life was changed by hearing Patti Smith’s music. How do you try to keep the spirit of those days alive in your life and work?

A: Patti Smith is a great role model. She triumphed as an artist, became a wife and mother, remained true to her friend and soulmate, and never seems to have compromised what she believes in, as both an artist and someone with a family — her late husband; her children; her siblings and parents and friends and bandmates. I think it’s important to remember that what you do on your home turf is at least as important as what you do in your art.

I try to maintain a certain integrity in what I write. I set the bar very high for myself, and I often fail, and I’m hard on myself for failing. But I try again and attempt, in Beckett’s words, to fail better. I write slowly and made the decision a few years ago not to write anything that I didn’t have my heart in 100%. So no more media tie-in work. I do a lot of teaching these days, which is one way to pass on the creative flame and encourage new writers. And I’m an activist on a very local, grassroots level — I try to be involved in issues in our very small community here in rural Maine.

A lot of early punk’s energy and rage was fueled by disillusionment — the realization that the hopeful visions of the 1960s weren’t going to come to pass, and that so many elements of the hippie movement were immediately swallowed then disgorged by media and corporate interests — flower children singing “I’d like to buy the world a Coke.”

And god knows, there’s still enough disillusionment to go around. I keep waiting for today’s kids to get riled up about the political situation and the world they’re going to inherit — riled up in a positive way, not in the rioting that we saw in the UK last year.

I still listen to the music from that time. I listen to a lot of other stuff, too, but I still get goosebumps when I hear the opening guitar solo to “Sweet Jane” on Rock & Roll Animal.

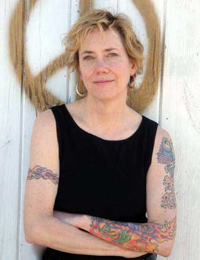

Q: Having dug out my old copy of Waking the Moon and seeing your author photo I have to ask you one more question. When did you get your tattoos and does each one have a special significance?

I wanted to get a tattoo since I was nineteen, when a boyfriend had a tattoo of a small gold ring with the letters PRB inside it, for Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. But people didn’t get tattoos then, even guys — you just never saw them except on old men.

I got my first one in 2001, right after Joey Ramone died. That was when it really hit me, that my generation was disappearing before my eyes. I thought What the hell am I waiting for?

So I went to a brilliant artist here in Maine (she’s since hung up her needle gun, alas) and asked for a ring of fire on my upper right arm. It’s from Lou Reed’s Magic and Loss, the song “The Summation,” which is probably the best song ever written about the struggle to be an artist — its central metaphor is of passing through a wall of fire.

The “Too Tough to Die” tattoo that covers my upper left arm is Cass’s, and I got it for the same reason she got hers.

On my calf I have the Dionysian figure of the Boy in the Tree, who recurs throughout much of my work. It’s based on an illustration from the Japanese edition of my novel Winterlong. It’s now also an homage to the dear friend who inspired the Boy in the Tree and Illyria, among other stories, and who died suddenly last year. He loved the tattoo, so I’m glad he got to see it.

The final tattoo is the most elaborate — it covers my lower left arm. It’s a quote from Rimbaud, set against a pattern of entwined vines and flowers on a background of flames, and took several months to do. (It’s actually still not quite finished.) The verse is from Rimbaud’s “A Season in Hell”; it’s in French, but here’s an English translation:

My eternal soul

Seize your desire

Despite the night

And the day on fire.

It’s a reminder to stay the course with my life and work.

Interview of Elizabeth Hand by Jamie Agnew.