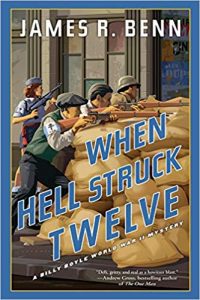

James R. Benn, the creator of the Billy Boyle series, agreed to answer a few questions about his wonderful WWII set novels. His newest book, When Hell Struck Twelve, will be published in September.

Robin: How did you come up with the initial idea to have Billy be Eisenhower’s nephew?

Jim: I wanted to create a mechanism that would allow Billy Boyle to follow the course of the war in Europe (and beyond) and to be close to major events. Having him work out of Eisenhower’s headquarters gives him carte blanche to go anywhere I need him to go. The notion of his being Ike’s nephew provides the opportunity to humanize Eisenhower through their occasional interactions; it was also the mechanism to explain Billy’s ascendancy to the lofty realms of high command, since Uncle Ike wanted a trusted family member to run his investigations into low crimes in high places. The relationship also explains how a lowly lieutenant, later captain, can act with relative impunity within the  chain of command.

chain of command.

Robin: I love that in your books you illuminate some of the more obscure parts of WWII history. In this latest novel, it’s the battle that opens the book. Can you talk about why you chose that battle, and tell us a little bit about it?

Jim: Yes, the incredibly brave stand of the Free Poles at Hill 262. This came at a critical time in later stages of the battle for Normandy, as the Allies tried to trap the retreating German forces. Patton’s American army was sent sweeping south to envelop the Germans, while the Canadian army attacked from the north. It was supposed to be a classic pincer movement, bagging tens of thousands of the enemy. But the trap was never fully closed, except for the Polish 1st Armored Division, which took Mont Ormel (Hill 262) overlooking the only road the Germans could take. They were basically surrounded, but gave the Germans a terrific pounding, and greatly slowed their retreat. But they died in the hundreds doing so.

I had two reasons for opening the book with this battle. First, I was struck by the fact that this fight occurred right after the Polish Warsaw Uprising, which saw tens of thousands of Poles killed, often at the hands of the SS. The Free Poles fighting SS troops in Normandy must have felt tremendous grief, anger, hatred, and a sense of just revenge as they engaged in bloody fighting with diehard Nazis on that hill. That was a story I wanted to tell. Secondly, Billy’s great and good friend Lieutenant Piotr Kazimierz is Polish, and I wanted him to be on that hill with his comrades.

Robin: When you are putting real people into the stories, is that a bigger challenge than creating them yourself?

Jim: The challenge lies in linking their true nature to the situation in the narrative. When placing historical figures in cameo roles, it’s important to show what they were like in a way that doesn’t bog down the story. One example is when Billy encounters General Patton, who gives him a dressing down for being out of uniform, then changes his tune when he finds out Billy is related to Ike. Patton knew he had to stay in Eisenhower’s good graces, so he gave Billy a break. That brief interaction shows two sides of Patton’s character.

Robin: In this book, you give the reader a different slant on Hemingway. He’s such an icon and you skewer him, I’m feeling righteously, a bit. Can you talk about this depiction of him?

Jim: The young Ernest Hemingway was a hugely talented and innovative writer. His short story “Big Two-Hearted River” is a masterpiece and broke new narrative ground. It’s genius. But as he grew older, Hemingway became a self-centered bully. He endangered other war correspondents by engaging in combat (or so he claimed). One reporter said correspondents like Ernie Pyle wrote about GIs at war, while Hemingway wrote about Ernest Hemingway at war. I initially thought he would be a more sympathetic and important character, but ultimately, he failed to come alive on the page as anything but a caricature of himself.

Robin: One of the strongest parts of your novels are the action scenes. I’ve read mysteries for my entire life so I feel I’ve read every action scene on offer, but you seem to add something new to the mix, maybe it’s simply the setting. Can you talk about structuring an action scene? Do you edit, edit, edit to get then to move the way they should?

Jim: Everything I know about writing action scenes I learned from watching Akria Kurasowa’s masterpiece Ran. There are moments of intense action in his battle scenes in which the sound disappears and all you are left with is the swirl of colors and violence, allowing your visual sense to take in the impact of what is happening. By the time I write an action scene, I have visualized it enough that I don’t need to think about structure; it’s all there, vivid and real in my mind. Emptying it out onto the keyboard is all that’s left. Of course there’s tightening up and edits to be done, but the essential truth of the scene is already there.

Robin: Do you read any of the other WWII novels that are out there, or does that pollute your own vision?

Jim: I’m not worried about that. I’d happily read a good book set during the war and watch for tidbits of atmosphere and details of everyday life to use, but such most novels don’t delve that deeply into the kind of research I’m after. Most of my reading is non-fiction, gathering data for the next book. Right now, I’m reading everything I can about the war in Russia, particularly in terms of the average Soviet soldier (that’s a hint. Station 559 in 2021 will take Billy and friends to the USSR).

Robin: When you start a novel, what kicks it off for you? A bit of history, or a narrative idea?

Jim: There’s nothing like finding a small fact, hidden away in a footnote, that opens up a world of narrative possibilities. That happened with The Devouring, when I came across a brief mention of a Zionist underground youth organization what smuggled Jewish children into Switzerland. I’d never heard of that, and then was shocked to learn they had to evade not only the German border guards, but the Swiss as well, because Switzerland did not want to take in Jewish refugees. For When Hell Struck Twelve, it was the realization that the Liberation of Paris almost never happened, and certainly wasn’t planned for by Eisenhower. Throw the German proclivity for Pervitin – methamphetamine – and it’s a heady mix. In addition, I cooked up a scheme with Cara Black for Billy to meet Claude Leduc, founder of Leduc Detective. That was a lot of fun.

Robin: Billy and Kaz are pretty physically and spiritually beat up by this point in the war. What’s ahead for them? Will they get a little R & R?

Jim: Not exactly R&R. Next year’s book, The Red Horse, finds them at a secret military hospital in England, run by the Special Operations Executive. This facility was inspired by the real-life Inverlair House in Scotland, where SOE kept agents who knew too much. Interestingly, a British writer named George Markstein wrote a novel based on Inverlair House titled The Cooler. He later teamed up with Patrick McGoohan and created the cult classic The Prisoner, which was inspired by SOE’s home for wayward spies. The Prisoner was filmed in the same town as Doc Martin, but I digress.

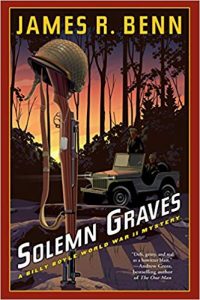

There’s a deeper answer to this question, in terms of writing a series and keeping it fresh. This book and the previous Solemn Graves both take place during the Normandy fighting, and both feature combat and battle scenes. I think it’s important to vary the setting and tone of each book, to keep the series reader interested. There was good reason to have those two books as a pair, but I thought it was time to modulate the experience and place the protagonists in a different setting, one that could be easily differentiated. Given all they go through in Paris, it seemed logical to get them some medical help, which places them in an entirely different and closed environment. So, The Red Horse (2020) will be different; creepy and a bit gothic. With V2 rockets falling on England, of course.

There’s a deeper answer to this question, in terms of writing a series and keeping it fresh. This book and the previous Solemn Graves both take place during the Normandy fighting, and both feature combat and battle scenes. I think it’s important to vary the setting and tone of each book, to keep the series reader interested. There was good reason to have those two books as a pair, but I thought it was time to modulate the experience and place the protagonists in a different setting, one that could be easily differentiated. Given all they go through in Paris, it seemed logical to get them some medical help, which places them in an entirely different and closed environment. So, The Red Horse (2020) will be different; creepy and a bit gothic. With V2 rockets falling on England, of course.

Robin: You’ve just liberated Paris, on the page, so the end of the war isn’t too far off. Do you anticipate getting to the end of the war, and if so, what happens to Billy?

Jim: I’m not worried. There’s plenty of war left. Station 559 will bring us to early October 1944. Then I’m thinking about a visit with the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the Japanese-American (Nisei) contingent which was the most decorated unit in the US Army. Then, the Battle of the Bulge and months more of fighting to go. I also have a feeling Billy is going to get stuck with some post-war duties in Berlin and Prague.

Robin: Finally, what writers and book have been influential to you in creating this wonderful series?

There are two who have greatly influenced me.

The first is Dalton Trumbo, whose Johnny Got His Gun taught me the power of the interior voice. For those who aren’t familiar, it’s the story of a First World War soldier who is so horribly maimed he has no limbs, no face, no way to communicate. The entire book is told from within his mind. Anybody who wants to write in the first person could benefit from reading this award-winning novel.

There’s a lot of Paul Fussell in Billy Boyle. Fussell was an infantry officer in Europe during the war. He saw combat and was wounded. He became a college professor and wrote widely on both world wars. His Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War revealed a new way of looking at the war for me, along with The Boys’ Crusade: The American Infantry in Northwestern Europe, 1944–1945. Fussell was a cynic and iconoclast who had no time for the romantic myths and notions of war as he knew it. He told the truth about the combat he saw in a way that had not been done before. He was unimpressed by officers, even though he was a lieutenant himself. Whenever Billy takes a dim view of a pompous senior officer, that’s a homage the spirit of Paul Fussell.

Hmmm. That just gave me an idea. I think Billy and Lt. Fussell have to meet up on the Siegfried Line.

Thank you so much, Jim!

A James R. Benn Reading List

Billy Boyle

The First Wave

Blood Alone

Evil for Evil

Rag and Bone

A Mortal Terror

Death’s Door

A Blind Goddess

The Rest is Silence

The White Ghost

Blue Madonna

The Devouring

Solemn Graves