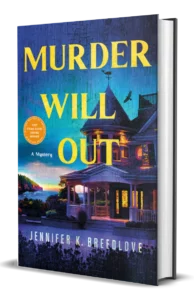

Jennifer Breedlove’s first novel, Murder Will Out, is already a favorite read of 2026 for me. The main character is a church organist who returns to her childhood summer place for a funeral and finds all kinds of intrigue and even ghosts. The writing, plotting and characters are all lovely. It deservedly won the Minotaur/Mystery Writers of America First Crime Novel Award. Jennifer graciously agreed to answer some questions.

Q: This is your first published book – but is it your first book? Are there novels stuck in a desk drawer somewhere, and this is the one that made it through? I ask because your voice seems both very assured and natural.

Q: This is your first published book – but is it your first book? Are there novels stuck in a desk drawer somewhere, and this is the one that made it through? I ask because your voice seems both very assured and natural.

A: Thank you so much for that; it is my first novel, or more to the point, the first novel I ever finished. I have dozens of partials floating around my house and computer, but this is the first one I made it to the end of. I wrote one novella when I was in college—it was schmaltzy and derivative and not very good at all by any empirical standard, but it was probably the most fun I’d ever had in my life up to that point. I’ve written several nonfiction books about music learning for adults, and lots of articles, but this is my first long work of fiction.

Q: I loved Willow’s backstory that comes through even before she gets to Little North – the fact that she’s an organist and a grad student. Can you talk about the thought behind creating Willow as a musician?

A: I worked as a professional church musician for over thirty years, though I was never much of an organist—certainly nowhere near Willow’s level. And I currently teach music and conduct in the choral program at Loyola University in Chicago. The chapel where Willow practices in the first chapter is loosely based on our campus chapel, right beside Lake Michigan. Music and academia are both big comfort zones for me, so it felt right to begin Willow’s journey there and then immediately pull her out of that comfort zone. A lesser reason, though still a real one: the concert organist profession has been male-dominated for centuries, though the balance is finally beginning to shift. It made me happy to put Willow in this field, as a wink to the amazing women I know who are out there playing at incredibly high levels.

The possibility of Willow playing for church weddings and funerals on the island also offers interesting opportunities for future books. I’ve played for probably hundreds of weddings and funerals myself, and dozens of baptisms, and believe me when I say there’s a lot of emotion in these life-passage gatherings, emotion that sometimes manifests as friction and discord. Don’t get me wrong—it’s a real privilege to be with families for these important moments, and most go very smoothly. But sometimes feelings run high, and not always in the directions you’d expect them to. I’ve been part of funerals that felt like truly joyful celebrations of life, and I’ve played for weddings so charged you could cut the tension in the air with a knife. It’s all such ripe territory for the kind of domestic drama and buried grievances that make for wonderful mysteries. Trust me, I could tell some stories…;-)

Q: I also loved the setting which adds so much to the story. Can you talk about Maine, why you set your book there, and what it means to you?

A: My family has visited Mount Desert Island in Maine, near Acadia National Park, for as long as I can remember; we camped up there every summer through most of my childhood. After my folks retired, they bought a little log cabin on the quiet side of the island; that cabin is the model for Aunt Sue’s cabin in the book, and Willow’s little loft bedroom is where I stayed when I visited them.

There’s something magical about that part of Maine, the rocky wildness of it all. When you cross over from the mainland, the air itself changes; nowhere else on earth, I’m convinced, has air that tastes like the air on that island, that particular mixture of balsam and ocean and wildflowers and woodsmoke…When the sun is out, the colors—sky, water, trees, flowers—all seem somehow more vivid than anywhere else. Even the fog and rain have this strange wild beauty, though I’ll own it was harder to appreciate when I was a teenager staying in a tent with my perpetually damp sleeping bag. The campground where we stayed was close enough to the coast that you could fall asleep listening to the slow roar of the sea and the song of the bell buoys that warned ships off the rocks.

Early in Murder Will Out, Willow muses how Chicagoans who regard Lake Michigan as “just like the ocean” have probably never visited that part of Maine; that thought is absolutely from me. I love Lake Michigan, I love my adopted city, and our lake, but…the ocean is different. I never feel entirely whole when I’m away from it for too long.

Q: Big question: why make it a ghost story? As I mentioned, it did make me think of Barbara Michaels as the ghosts weren’t totally scary (or really scary at all, except in one scene). This felt, and I mean this as a compliment, delightfully old fashioned.

A: I can’t tell you what a delight it is to me that you mention Barbara Michaels; she was one of my favorite authors for years, and I gobbled up everything I could find by her when I was young. I grew up on those old-school Gothic novels—Michaels, Daphne duMaurier, Victoria Holt, Phyllis Whitney, and so on. I don’t remember if I just happened upon them or if my mom steered me to her own bookshelf when my voracious appetite for books outpaced my and my parents’ budget to keep me supplied, but I loved those novels. What’s funny is that I didn’t even see the (now-obvious) connection until you made the comparison; those books must have been more formative for me than I realized.

A: I can’t tell you what a delight it is to me that you mention Barbara Michaels; she was one of my favorite authors for years, and I gobbled up everything I could find by her when I was young. I grew up on those old-school Gothic novels—Michaels, Daphne duMaurier, Victoria Holt, Phyllis Whitney, and so on. I don’t remember if I just happened upon them or if my mom steered me to her own bookshelf when my voracious appetite for books outpaced my and my parents’ budget to keep me supplied, but I loved those novels. What’s funny is that I didn’t even see the (now-obvious) connection until you made the comparison; those books must have been more formative for me than I realized.

As for the ghosts…The first seeds of this story took root in my head shortly after I lost two people very close to me, within a week of each other. I expected the grief, but I didn’t expect the way my mind would hold onto the reality of who they were, to the point of sometimes almost forgetting they were gone. Conversations as though they were in the car with me, feeling the sense of someone sitting in the chair across the room…

We tend to talk about spirits and “hauntings” as though they are this strange and supernatural thing, but in a way, isn’t holding and sensing the spirits of the people who shaped us, surrounding us all the time, one of the most natural things in the world? Memory, in its realest sense, can be like visiting the past and bringing some part of it into the present—a sort of time travel, if you will, where then and now meet and interact on the same ground. So Murder Will Out embraces that dynamic and dials it up about seven notches, with the ghosts of the Cameron family serving as the active (and very opinionated) memory of the house and village. They have their own aspirations and goals, and they are happy to interfere with the lives of the living when the situation calls for it.

There are a couple moments in the book where the narrative is ambiguous about whether a character is meeting a “ghost,” or simply experiencing this kind of intense and present memory. That was deliberate.

Q: I liked all the human connections – and the misunderstandings that come with them – between the characters on Little North Island. That seems like a difficult thing to create, especially when you are creating many characters that are very different from one another. Some writers have what I call “mushy” or unmemorable secondary characters, but you seem to have avoided that trap. Can you talk about creating this community?

A: The one universal truth of humanity is, I think, that people are complicated. Almost no one is “all good” or “all bad”—the sweetest and most lovely person you’ll ever meet has a gritty side; the biggest jerk in town might be a complete teddy bear under the right circumstances.

My side characters often begin life as little more than NPCs in a video game—they fulfill a purpose, but they’re pretty flat and boring. Then at some point, a door will crack open just a little; a character will surprise me, and suddenly they become three-dimensional. For example: there’s a moment in the book where two characters are in a pub, and a waiter comes over to take their order. The externally flawless image-conscious woman we expect to decline sets her bourbon down and says, “I’ve had an awful day; bring me a brownie sundae.” I wasn’t expecting that; she surprised me. With that one tiny detail, she suddenly became much more interesting, and real. Any character that doesn’t experience some version of this transformation by the end of the first draft is likely to be cut from the second.

Q: Another trick that appears to come to you naturally is drawing emotion from the reader. Again, not every writer can do that, but I ended this one with a box of Kleenex at my side. What do you draw on to create this kind of emotional resonance?

A: Oof, that’s one of the hardest things for me, and it’s something I’m very self-conscious about—so I’m happy to hear that it succeeded for you. I’m an inveterate weeper—I don’t wait for the sad ending of the movie to start crying, I am usually grabbing the tissues at the beginning. I suspect the places in the book where the emotion runs deepest are the ones that touch on places where I’m pretty tender myself. That said, it usually takes several drafts of an intense scene to peel away the self-protective layers and find the real emotion at its heart.

Q: What’s your approach to plotting? What’s most important when you start out – the plot, the characters, or the setting? I thought all three were strong here.

A: Thank you! I tend to focus first on the mystery part of the plot; that piece can be logical, structural, clinical even—the intellectual challenge of crafting a worthy puzzle, with the basics of who, how, and why-dunit. This is the part of “writing” where I do a lot of wandering around the house or walking the dog, mumbling to myself, with a vague and vacant look in my eyes. I’m sure my family loves that part. That’s where the story finds its over-arching structure, the skeleton that I can drape everything else on.

Then I work out the details of my characters, with whatever warts and insecurities they bring to the world. I do a lot of pre-writing—I like to get the characters as developed and layered as possible before I start the actual manuscript. It’s slow at first, but once I have a cast of fleshed-out characters, I can drop them into the puzzle, set them loose in the world of the story, and let them react in whatever way their personalities suggest. And, as I noted, even the ones I think I know best usually manage to surprise me.

So I guess, in answer to your question, I like to develop each element separately before I put them together in the world of the story.

Q: Some would call this novel a cozy – it has an inheritance, the return to town of the ingenue, even the cute dog – though I’d call this book a “hard” cozy, fitting with work by writers like Ellen Hart, Julia Spencer-Fleming, G.M. Malliet and Connie Berry. What are your thoughts on categories, and where do you feel your book fits?

A: I don’t think I’d be capable of writing in any genre without a cute dog. But honestly? Especially when I’m drafting, I try hard not to think overmuch about categories, and write the story that needs to be written. When I started the first draft of Murder Will Out, I thought it would be a cozy, but it took a turn somewhere and wound up something…else. I worried about that for a while, but eventually I had to let it be what it was—and I was much happier once I did.

I feel like there’s a trend lately of books that are sort of “cozy-adjacent”—they have some of the vibe of a cozy, but they go a little out of the box. I absolutely love Olivia Blacke’s Ruby and Cordelia mysteries, where a ghost who died in her apartment teams up with the naive Gen-Z tenant who moves in after her death to solve crimes. They have a cozy-ish vibe in some ways, but the world of the novels is darker and the crimes grittier than a cozy would permit, and the fact that Cordelia is a ghost keeps that death-shadow in the forefront even through the charm and humor. Gigi Pandian’s Secret Staircase books too, and Kemper Donovan’s Ghostwriter Mysteries, some of my other favorites—I feel like all of these have at their core a sense of warmth, a web of connection and friendships, especially among people who start out prickly and isolated but are drawn into relationship with the other characters in spite of themselves. There’s danger, and death, and all the necessary elements of a good mystery, but the heart of the energy in these books comes from the interconnected characters.

Q: Can you name a book that was transformational to you as a reader or a writer, and why?

A: This might seem like a strange one, but…when I was little, my grandmother had this gorgeously bound book of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, with hauntingly beautiful illustrations. It was one of those books you knew, even as a child, to handle carefully—I remember feeling like it was sacred or something, with its gilt edging and silky-smooth pages. I used to stay with my grandparents often, and I would read and reread those stories over and over till I could recite long passages from memory.

It didn’t occur to me till much later, but I think even as a child I was drawn by the way these stories offered wonder and magic on the one hand, and then tragedy and loss and casual cruelty on the other—I mean, go back and read “The Fir Tree,” and you’ll never look at your Christmas tree the same way again. The way the glory and the heartbreak intertwine is full of such fragile beauty, and Andersen makes the juxtaposition feel so…inevitable. I really do believe the stories we read shape the way we see the world around us, and I was decades older before I realized how much that book shaped the way I conceive of existence in general.

Q: And what’s next? Will there be another book featuring Willow – I hope?

A: That’s the plan! It’s hard to say much without giving spoilers for the way Murder Will Out ends (though I guess I did hint earlier about the possibility of a mystery at a wedding or a funeral), but there are a lot of possibilities for Willow and Cameron House. The folks on Little North Island are too interesting not to visit again, and I’m having a wonderful time digging into the histories of some of the ghosts we haven’t really met yet.

*******************

Jennifer Breedlove holds degrees in piano, choral conducting, and theology; she is on the music faculty at Loyola University in Chicago and serves as an assistant conductor for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Chorus. Jennifer has worked as a church musician, educator, and editor and is a prolific composer of choral music; her compositions, as well as her nonfiction books and articles, are available through several major publishers. A frequent visitor to Downeast Maine since childhood, she has an enduring affection for the wild beauty of the coastal islands and the warmth of the people who make their homes there. Her debut novel, Murder Will Out, won the Minotaur Books/Mystery Writers of America First Crime Novel Award, and was also a finalist for the Killer Nashville Claymore award.

She lives in the western suburbs of Chicago with her husband, two dogs, and two kids currently attending college. Demonstrating once again the cliché about apples and trees, her son is a music major, and her daughter plans to be a writer.