I absolutely loved R.P. O’Donnell’s first novel, No Comfort for the Dead, set in tiny Castlefreke, Ireland. The book follows the journey of the town librarian, Emma, and it’s an evocative, beautifully written and felt novel. This is a writer who is giving readers much to enjoy, and much to look forward to. The lovely prose reminded me of Louise Penny. This is not a book to be missed! I was delighted when he agreed to answer a few questions.

I absolutely loved R.P. O’Donnell’s first novel, No Comfort for the Dead, set in tiny Castlefreke, Ireland. The book follows the journey of the town librarian, Emma, and it’s an evocative, beautifully written and felt novel. This is a writer who is giving readers much to enjoy, and much to look forward to. The lovely prose reminded me of Louise Penny. This is not a book to be missed! I was delighted when he agreed to answer a few questions.

Q: First of all, let me just say I loved the book. One of the reasons was character, especially Emma. Can you talk about how you developed your characters and populated the story?

A: Thank you so much! And thank you so much for the interview.

I build my characters bit by bit. They start as a vague idea — a young burnt-out woman, for example, or a lonely widow in a small village. And from there, I experiment. I add on bits of my own personality, or stories I’ve overheard, and see if it fits. It’s electric when you discover the reason a character behaves a certain way — even though you’re the one who’s created the character in the first place. To discover that a cranky old woman is actually that way because she’s still grieving the love of her life forty years later. And then to discover that she’s the one who went down to the shore with her father at 8 years old, searching for survivors from a shipwreck. That’s what excites me about writing — getting closer to understanding people.

Q: I loved the character of Mary. She’s such a surprise in many ways. Can you talk about her a bit?

A: Mary was a surprise to me too! She began as a foil to Frances and Emma, but then took on a life of her own. I think it’s because when we meet her, I wanted the reader to write her off as quickly as the other characters do. So when we realise just how much there is to this woman, it’s a revelation for everyone.

Out of all my characters, Mary is the least like me, personality-wise. And not just because I hate boiled sweets. But I have a great compassion for, and understanding of, her deep loneliness. It can sometimes feel like grief and loneliness can drown out everything good about a person. And it’s much easier to just write people like that off, to tell ourselves, well, they’re just unpleasant and move on. But really, we all need to look harder at the people we see around us. And at ourselves. To be curious, not judgmental, as Walt Whitman definitely did not say. A challenge for people to say ‘Hello in There’, as John Prine on the other hand did say.

Q: Why set your book in the 80’s?

A: Because I hate digital technology. (Just kidding.)

In 1988, The Economist wrote that Ireland was doomed. It was essentially a call to take the country’s economy behind the woodshed and just be done with it. The game was over, they declared, and there was no possible chance at recovery. But then, just 10 years later, Ireland was in the midst of the Celtic Tiger — one of the world’s greatest underdog stories. Until, of course, just 10 years after that, and 2008 Ireland was one of the world’s largest economic craters, revealing just how much of a sham the Celtic Tiger had been all along.

And it wasn’t just the economy. The Troubles had calmed down in the mid-80s, but then in March 1988, three IRA members were shot dead in Gibraltar. And that led to a series of unfortunate and escalating events. Suddenly, the calm was gone.

So, 1988 in Ireland was a watershed moment. The year it changed completely. I thought it was an interesting time to start a story — to see characters go through change while the world around them takes the first step off a cliff.

And I also hate digital technology. I recently bought a cassette tape recorder.

Q: I really liked the various symbols throughout the book – the foxes and the bats. Can you talk about what those might mean and why you chose those in particular?

A: They represent the idea of the wild breaking through into everyday life. The unpredictability of nature, and of life itself, and how that can be both beautiful and dangerous. Before I say this, I have to stress that there is much, much more to West Cork than just farming and fishing. But even for the majority of people who are not farmers or fishermen, we’re constantly surrounded by it. And when you’re surrounded by it, you start to see nature’s clock — foaling season, leaves changing colour, harvest time, etc. These days, we see a chance encounter with a wild animal, or with fate, as just that. A chance encounter. But really, it’s part of a much larger cycle — the chiming of a clock we can’t hear.

Q: I know this is your first novel, though you have worked as a journalist. Not an uncommon switch up for a crime writer. Have you always wanted to be a novelist? How long was your path to publication?

A: I wasn’t actually a journalist! Just a freelance writer for some newspapers here. What drew me to it was that being freelance meant that I could write about anything I wanted, and I didn’t have to be tied down into one specific area. I’ve always been curious in a million different directions. I wrote about health, history, politics, social media, women’s rights, childhood, and more. I think it’s that curiosity and, ironically, its accompanying lack of focus that has helped me be a better novelist.

I actually never wanted to be a novelist growing up. My parents were huge readers, and they gave that to us. Growing up, we were only allowed a half hour of TV a week, and me and my four older siblings had to agree collectively on what we watched for that half hour. So I read everything. Almost every author interview I’ve seen, they’ve usually said something similar — they were big readers growing up, and then one day, it clicked that they wanted to be one of those authors. For some reason, that never happened for me. I wrote poetry and music all the time, but never considered writing an actual book. It was once I moved to Ireland that it clicked — I wanted to write a book.

Q: I see you were born in America but moved to Ireland. Is the village where you live similar to Castlefreke? The setting and atmosphere are really lovely and help make the book a standout.

A: I have to answer this one very carefully! The physical layout of the village is identical to the village I live in. You can walk though the village and point out the real buildings where all of the characters live — the Castlefreke library is the old post office, for example, and Emma and Sam live in my old house. I don’t have a visual brain, so it was much easier for me to just populate a real village with imaginary people. But the characters and villagers are completely made up, and have no bearing on the real people of the village. As someone living in a small village, I just really have to emphasise that point.

Q: While this book has many elements of a cozy – small village, town librarian main character, off the page violence – it’s more of a dark or traditional cozy. Do you view this book as a cozy? Or is that mainly an American phrase?

A: I don’t think of it as cozy, but not because there’s anything wrong with cozy crime. I don’t want to sound pretentious, but I think genres are unhelpful. My favourite books are ones that are grouped, at least here, into the genre of Commercial Women’s Fiction. And the range of books that this very unhelpful designation encompasses is insane. I wrote this book for my kids — so that 30 years from now, they’ll be able to hold something that tells them what I valued, what I loved, and what I thought was important. And I’ve always believed that, in everyone, there is good. So, the book was probably always going to turn out at least cozy-adjacent.

Q: Who are your writing influences? Have you always read mysteries?

A: As I was starting to write this, people asked and I said no, I don’t read mysteries. Until somebody pointed out that the Sherlock Holmes adventures are mysteries. The story in the book of how she read her anthology of Sherlock Holmes until it fell apart, starting it over as soon as she finished it — that’s me. (I’m on my third copy now.) But Maeve’s rant about how the adventures are not actually mysteries, because Sherlock is really just a superhero for nerdy kids — I wrote that because people in my real life were getting tired of hearing me say it over and over, unprompted. So it never clicked that I was a mystery lover.

But once I decided to write a mystery, I started actively searching them out, reading more and more. I think it was helpful, both that I read a lot of them, but also that I came to it later, after I’d decided the story and characters. So I could learn, rather than try to emulate.

Q: The prose is another element that made this book a standout, and I loved the almost fey quality of the writing. How important is prose to you in creating a kind of emotional resonance for the reader?

A: I love that word, fey. And that was a deliberate choice, because that’s how I find the world. My favourite series is the Twilight Zone. People think it’s a sci-fi show, but mostly it’s about how thin the division between the real world and something more mystical really is. And especially in West Cork. The story at the end, about the lights in Castlefreke, is a true story.

One of my all-time favourite authors, Caroline O’Donoghue, says that all authors are one of three things: a director, a musician, or a stand-up comedian — in terms of what they value and emphasize as writers. I am definitely a musician.

To try to explain it, my whole family is obsessed with Scrabble. I absolutely love board games — but for some reason, Scrabble never interested me. Which is odd, for someone who reads and writes as much as me. But I later realised that the reason Scrabble never interested me is because I’m not actually interested in individual words. Words for me are like individual musical notes. Musicians don’t say, you know, I just love a C#m. It’s when you combine those notes in certain combinations, and turn them into a song — that’s where the magic is.

Q: What’s next for you? Do you have a long arc in mind for Emma?

A: I do indeed! I’m not done with Castlefreke or Emma yet. I’m currently working on a sequel that I’m really excited about. It takes place a few months after No Comfort for the Dead, in the wake of all the changes in the village.

Q: Finally, can you talk about a book that was transformational for you as a writer or a reader?

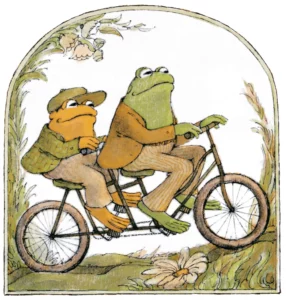

A: It’s going to sound silly, but I’m obsessed with the children’s series, Frog and Toad by Arnold Lobel. Mainly because I want to live in their world, and I love both the messages and the aesthetic. But in terms of writing, it’s an interview with Lobel that changed me as a writer. He said once that both Frog and Toad are different sides of his personality. Basically, that he wanted to understand himself better, by writing these two very different characters. It sounds very simple, but as they say, common sense isn’t always common practice. That message became my approach to character, which is how I approach writing.

A: It’s going to sound silly, but I’m obsessed with the children’s series, Frog and Toad by Arnold Lobel. Mainly because I want to live in their world, and I love both the messages and the aesthetic. But in terms of writing, it’s an interview with Lobel that changed me as a writer. He said once that both Frog and Toad are different sides of his personality. Basically, that he wanted to understand himself better, by writing these two very different characters. It sounds very simple, but as they say, common sense isn’t always common practice. That message became my approach to character, which is how I approach writing.

And Caroline O’Donoghue, Douglas Adams, John Cheever, and Maeve Binchy. They all changed my life, as well as my writing.

***********************

R. P. O’Donnell grew up on the South Shore of Boston. He was short and wore a back brace for two years, so he really had no choice but to love reading and writing from a young age. He graduated from Bucknell University with a degree in English. He’s had a wide range of job experiences: garbage collector, A&E admissions, apprentice to a roving yard-sale salesman, barista, camp counsellor, caterer and a call centre employee. He moved to a tiny fishing village in West Cork seven years ago, where he lives with his two children. His debut mystery, No Comfort for the Dead, also set in a village in West Cork, is forthcoming from New Island Press (UK) and Crooked Lane (US).

R. P. O’Donnell grew up on the South Shore of Boston. He was short and wore a back brace for two years, so he really had no choice but to love reading and writing from a young age. He graduated from Bucknell University with a degree in English. He’s had a wide range of job experiences: garbage collector, A&E admissions, apprentice to a roving yard-sale salesman, barista, camp counsellor, caterer and a call centre employee. He moved to a tiny fishing village in West Cork seven years ago, where he lives with his two children. His debut mystery, No Comfort for the Dead, also set in a village in West Cork, is forthcoming from New Island Press (UK) and Crooked Lane (US).