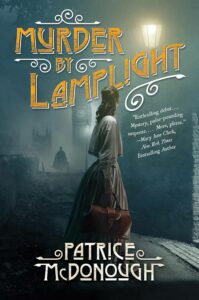

I really loved Patrice McDonough’s debut mystery, Murder by Lamplight, set in 1860’s London, and featuring a female doctor as the main character. Much like Anne Perry, she’s not afraid to tackle social issues, and also like Perry she supplies the reader with some wonderful characters (hard to believe this was a debut!). I am very much looking forward to more in the series, and Patrice was nice enough to answer some questions.

I really loved Patrice McDonough’s debut mystery, Murder by Lamplight, set in 1860’s London, and featuring a female doctor as the main character. Much like Anne Perry, she’s not afraid to tackle social issues, and also like Perry she supplies the reader with some wonderful characters (hard to believe this was a debut!). I am very much looking forward to more in the series, and Patrice was nice enough to answer some questions.

Q: I loved the main characters – as I think there are two, but let’s start with Julia. Talk about making her a doctor at that time. How many female doctors were there in London in 1866?

A: Julia Lewis is a role-breaking groundbreaker, and creating her was fun. In 1866, she would have been a rare bird indeed. No medical school in Britain admitted females, so Julia earned her degree from a women’s college in Philadelphia. In 1858, when Parliament added doctors with foreign degrees to the medical register, it unintentionally opened the door to female physicians. The fictional Julia would be one of three on the register in 1866.

In 1849, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in the U.S. to earn a medical degree. Ten years later, she was the first woman added to the British medical register. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson came next, exploiting another loophole by passing the Society of Apothecaries exam. In 1866, she opened a charity clinic and treated cholera patients during the London epidemic. So, there are bits of Blackwell and Garrett Anderson in the fictional Julia Lewis.

Some readers may find Julia’s attitudes too modern, but “strong-minded women” (I love that Victorian phrase for early British feminists) emerged in the 1850s and 60s. They demanded reforms to the legal system, the vote in Parliament (first proposed in 1867), and access to university education (Girton College, Cambridge, founded in 1869). Julia’s debates with Tennant about women’s roles are spot on for the novel’s 1866 setting.

Q: The other main character is Inspector Tennant, and you’ve gifted him with many challenges to work through. Can you talk about what went into creating his character?

A: I wrote Richard Tennant as a contrast to Julia in personality and personal history. Yet, he and Julia share things that draw them together. Julia was orphaned early but reared by loving grandparents and a caring, sometimes peppery, great aunt. Tennant is the product of an unhappy marriage and a cold, withholding mother. Other personal disappointments closed him down. I enjoyed writing Tennant’s gradual thawing and opening up.

Julia and Tennant bond over their “outsider status.” Julia is a female physician in Victorian England; Tennant has an elite background that alienates him from Scotland Yard’s working-class coppers. Yet, they soldier on, slowly winning each other’s respect. They also harbor past traumas that haunt them, and each has an inkling of the other’s inner struggles.

Q: I also appreciated the different parts of Victorian London you’ve shone a spotlight on, none of them too delicious – cholera, workhouses, “Molly” houses, abandoned children. What went into your research?

A: Ah . . . cholera. Here is where I confess to an odd fascination with disease in history. Name one—the black death, smallpox, cholera, the 1918 flu, polio—and I’ve read the book. (A cousin, aware of this, recently sent me a copy of Pox. I now know an awful lot about syphilis.) As for cholera, Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map tells the fascinating story of how Dr. John Snow solved the mystery of cholera’s spread.

I read two wonderful books about music halls: Richard Anthony Baker’s British Music Halls (his father was a performer) and Lee Jackson’s Palaces of Pleasure. Fewer work hours and higher wages gradually gave Victorians the time and means to enjoy themselves. Baker filled his book with stories about the leading performers, quotes from popular songs, and details about famous acts.

The literature on workhouses, both online and in print, is extensive. Parliamentary investigations and reports often followed workhouse scandals. The documents are sobering. And Dickens was a great resource. Readers will recall the scene in Oliver Twist when the young Oliver, “advancing to the [workhouse] master, basin and spoon in hand,” asks, “Please, sir, I want some more.”

Q: What did you leave out of your research? I know it’s probably difficult not to head down an interesting rabbit hole.

A: It may sound contradictory, but cholera got the ax. My original idea was to set the novel in the middle of the epidemic. The disease faded into the background as I worked on the manuscript. Fever hospitals and scenes of Julia treating victims at her clinic disappeared. The epidemic is over when the book begins, but its aftermath lingers and is an engine for the plot . . . or a giant red herring. (I’m dodging a spoiler here.) I began writing Murder by Lamplight in the fall of 2019—about six months before COVID-19 arrived in the U.S. Then six months into the pandemic, I was happy the book’s focus had shifted. When people live a nightmare, they probably don’t want to read about a similar one.

Q: I also liked the family you’ve surrounded Julia with. If you’re setting up a series, she has a good surround of community. Each one draws out different parts of her character – her aunt, her grandfather, the boy she finds work for and looks out for. Do you have a favorite? Plans to feature any/all of them in upcoming books?

A: I have two favorite supporting characters: Paddy O’Malley and Aunt Caroline (Lady Aldridge). Both characters return in the upcoming books. As I wrote them, I had the faces and personalities of two people in my head.

Tom Davis was my father’s NYPD partner before he became a detective and left the uniform branch. Like O’Malley, Tom was a “gentle giant,” big, kind, and soft-spoken. I slapped a bushy mustache on O’Malley, but he’s Tom Davis, through and through.

Mary McDonough Condon was my father’s sister, the oldest girl in a family of nine children. After she reared her brood of seven (including her two youngest twins!), she worked as the assistant to a New York hospital’s chief of staff. Like Julia’s Aunt Caroline, my Aunt Mary was handsome, elegant, smart, sometimes steely, and no-nonsense. She played golf into her late eighties and had a killer short game.

Q: I liked the blend of grimness – Victorian London, and the gruesome murders – and Julia’s loving family. There has to always be a spark of something not completely bleak, for me as a reader at least, or I’m not engaged enough to keep reading. Can you talk about setting up your story?

A: I wrote some scenes to take readers away from Whitechapel and the murders. The Wednesday night dinners, especially the second one that Tennant attends, allow playful moments—some banter, Julia messing about with Tennant’s tie. And I tried to give Julia a sense of humor as relief from her grim experiences.

Conversations with Aunt Caroline force Julia to grapple with what she wants from life. Work-life balance is still a problem for women, and Julia is at the dawn of it—at least for well-off females. Working-class women have always struggled with the juggling act of family care and wage earning.

A short scene I wrote and rewrote takes Tennant away from London and the investigation. Over Christmas, he walks the Kentish downs, exploring and clarifying his feelings for Julia. It’s one of my favorites.

Q: What do you feel you learned as a writer on your first book? What lessons are you going to take forward with you?

A:

1. That historical fiction requires a disciplined balance of reality and make-believe. Novels set in the past require “world-building”— or why not simply write the book in the present? But you can get carried away. It takes fortitude to tap the delete button and rid the manuscript of details you love but get in the way.

2. To make the supporting cast memorable. That was a big contribution from my wonderful literary agent, Jim Donovan, a gifted writer. Early on, my supporting characters were plot devices, not people. Jim said I could do better.

Q: What’s your favorite part of sitting down to write? Your least favorite?

A: Unless it’s “bucketing down,” as my Irish constable Paddy O’Malley would say, I start my writing day with a morning walk. I love it when I’ve talked some promising ideas into my phone’s notes and return home to write. And I love rewriting . . . a little too much. Is fiddling with chapter five for the twentieth time an edit too far? Not to me: I see nothing odd in the quote (attributed to Wilde and Flaubert), “I spent all morning putting in a comma and all afternoon taking it out.” Yep.

A: Unless it’s “bucketing down,” as my Irish constable Paddy O’Malley would say, I start my writing day with a morning walk. I love it when I’ve talked some promising ideas into my phone’s notes and return home to write. And I love rewriting . . . a little too much. Is fiddling with chapter five for the twentieth time an edit too far? Not to me: I see nothing odd in the quote (attributed to Wilde and Flaubert), “I spent all morning putting in a comma and all afternoon taking it out.” Yep.

My least favorite is writing myself into a dead end and knowing I have to throw away a bunch of pages—or chapters— and start over.

Q: Can you name a book that was transformational for you as a reader or writer? A book that set you on a path you wanted to explore?

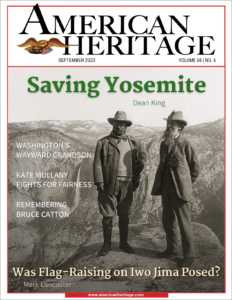

A: They were “books” to me in the 1960s and 70s because they arrived, bound in white hardback covers, every two months: my father’s American Heritage magazines. And I read them, white cover to white cover, eager for the next edition. They planted the seeds of my love of history. Undergraduate and graduate degrees followed, and I taught high school history for over three decades.

Q: And what’s next for Dr. Julia? What’s up your sleeve for the next book?

A: A Slash of Emerald, the second book in the Dr. Julia Lewis Mystery series, is set in the Victorian art world. A vandal targets the studios and galleries of London’s female artists, slicing canvases and splashing “Paris Green” paint. Then their models disappear and turn up dead.

Thank you, Patrice!