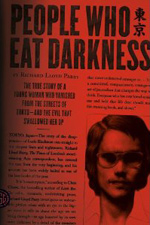

It’s no mystery—a book, any kind of book, has to contain certain key ingredients to be good and generally the more of these ingredients it has, the better it’s going to be. Look at the case of People Who Eat Darkness by Richard Lloyd Parry, which, although an example of the not always respected true crime genre, has more than enough of the right stuff to be a truly enthralling read.

Let’s start with plot, which, despite what the more literary than thou crowd says, is absolutely crucial, always has been, always will be. People Who Eat Darkness has a set up most thriller writers would kill for—Lucie Blackman, a twenty-one year old English blonde working in Japan as a bar hostess, goes on a date with a client (in Japan, as Parry explains, none of these terms require the ironic quotation marks they would over here) and fails to return. Her roommate, Louise Phillips, perturbed, asks around, learns nothing, contacts the disinterested police and eventually receives a disturbing phone call. The person on the other end says that Lucie is fine, but has decided to join a cult and has no interest in communicating with her old friends ever again. When Louise insists on speaking to her, the caller, a Japanese man, informs her that Lucie isn’t feeling very well at the moment and hangs up. He quickly calls back, saying Lucie is determined to start a new life and, by the way, what’s your address? He claims that he wants to return Lucie’s belongings, and when Louise points out that Lucie surely knows her own address, repeats that she’s not feeling well and can’t remember, and what did you say that address was again? A horrified Louise protests and the man hangs up for good.

Let’s start with plot, which, despite what the more literary than thou crowd says, is absolutely crucial, always has been, always will be. People Who Eat Darkness has a set up most thriller writers would kill for—Lucie Blackman, a twenty-one year old English blonde working in Japan as a bar hostess, goes on a date with a client (in Japan, as Parry explains, none of these terms require the ironic quotation marks they would over here) and fails to return. Her roommate, Louise Phillips, perturbed, asks around, learns nothing, contacts the disinterested police and eventually receives a disturbing phone call. The person on the other end says that Lucie is fine, but has decided to join a cult and has no interest in communicating with her old friends ever again. When Louise insists on speaking to her, the caller, a Japanese man, informs her that Lucie isn’t feeling very well at the moment and hangs up. He quickly calls back, saying Lucie is determined to start a new life and, by the way, what’s your address? He claims that he wants to return Lucie’s belongings, and when Louise points out that Lucie surely knows her own address, repeats that she’s not feeling well and can’t remember, and what did you say that address was again? A horrified Louise protests and the man hangs up for good.

Of course events are driven by character, and character in turn is revealed by events. Parry paints vivid portraits of killer and victim, or rather victims, as the impact of the horrific crime ripples out to affect entire families, communities and even nations. Some true crime books tend to idealize the victim, but here the loss of Lucie is even more poignant because of her imperfections—an insecure, somewhat naive young woman who stumbles into an evil few would anticipate.

Lucie’s family are also vividly portrayed. Her father, Joe, travels to Japan, working tirelessly to publicize her case and prod the authorities, yet also seems to enjoy the media spotlight a little too much, refusing to play the role of stereotypical grieving parent, and eventually, in a twist no fiction writer would dare attempt, commits a stunning act. His ex-wife Jane is more conventional, insisting on her privacy and snarling at the press, yet strangely determined to use the tragedy to further her personal vendetta against Joe. Her siblings and friends are also sharply defined by the glare of uncertainty and grief, as are, eventually, the friends and family of the killer.

But what about the killer himself? One of the reasons we read true crime is to try to comprehend the nature of a person who commit such crimes, but, brilliantly, Parry makes the criminals very impenetrability his defining feature:

Humans are conditioned to look for truth that is singular and focused, hanging for all to see like a clear, full moon in a cloudless sky. Books about crime are expected to deliver such a photographic image, to serve up a story as dry as a shelled and salted nut. But as a subject [the killer] sucked away brightness; all that was visible was smoke or haze, and the twinkle upon it of external light. The shell, in other words, was all that was to be had of the nut. But the surface of the shell turned out to be fascinating in itself.

As can be seen by the above excerpt, Parry’s prose is yet another strength, elastic enough to be journalistic or poetic as the narrative demands.

And then there’s the setting. As the most modernized Asian culture, Japan fascinates because it is so superficially familiar, yet so fundamentally foreign, and there’s nothing like a mysteriously missing gaijin to highlight the disconnects. Parry is the Asia editor and the Tokyo bureau chief of The London Times and the perfect tour guide for this complex and occasionally absurd and unexpectedly sordid scene.

Finally there’s the underrated quality of pacing. Even though People Who Eat Darkness is 434 pages and portrays long periods of uncertainty and seeming inactivity, Parry draws the reader through his narrative with artful flashbacks, fascinating asides, foreshadowing, and more than enough skill to make the sometimes tedious process of real world justice just as absorbing as any fictional counterpart.

The desired result of all these ingredients is, of course, enjoyment, and Parry has fashioned an enthralling, disquieting, entertaining and profound book—with the added kick—it’s all true.