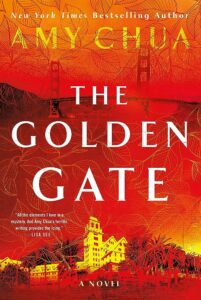

This is a first novel from Amy Chua, author of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, and it’s an ambitious and almost overstuffed concoction set in 1944 San Francisco. Peeling away the many, many complicated layers of her story, the essential plot line is this: in 1930, two sisters were playing at the Claremont Hotel while their mother played tennis. One of them dies by plunging down a laundry chute. Fast forward to 1944, and their grandmother is giving a deposition to the DA, who is sure one of her granddaughters (one of them the sister of the dead girl) is guilty of murder, and he doesn’t mind charging them all if he can’t get a straight answer from her.

This is a first novel from Amy Chua, author of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, and it’s an ambitious and almost overstuffed concoction set in 1944 San Francisco. Peeling away the many, many complicated layers of her story, the essential plot line is this: in 1930, two sisters were playing at the Claremont Hotel while their mother played tennis. One of them dies by plunging down a laundry chute. Fast forward to 1944, and their grandmother is giving a deposition to the DA, who is sure one of her granddaughters (one of them the sister of the dead girl) is guilty of murder, and he doesn’t mind charging them all if he can’t get a straight answer from her.

The murder: one Walter Wilkinson, unsuccessful candidate for president against FDR. It’s an easy transposition to imagine Chua is writing about Wendell Wilkie, who did die young, but of a more ordinary heart attack, not a mysterious murder in a hotel room where he was shot at once, moved rooms, and ultimately killed successfully.

It’s the background and setting that give the book it’s almost overstuffed richness. There’s the detective on the case, Al Sullivan – he has Americanized his name from Alejo Gutierrez as he is light skinned enough to “pass.” Much of the book centers on race and the sad fact of racial hatred, which, no matter the decade, is unchanged, it’s just that sometimes the targets of the hatred change. In 1944, much of it was directed at the Japanese after Pearl Harbor, and the US is living through the shame of Japanese internment camps. Al (or Alejo) is a smart, decent man, one who has some trouble with an ambitious boss who attempts to make every fact fit a pre-determined and convenient solution.

Then there’s Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, who indeed lived in the Claremont neighborhood from ’43 to’44. The fear of communism was as intense as fear of Nazis at that moment, and Chiang Kai-Shek was the opposite of Mao Tse Tung. Some clues around the body seem to point to a Chinese involved solution. Chua also shares much of the history of San Francisco – as the whites settled and ravaged the native otters for fur, the Sequoias for wood, and asserted white dominance over the native cultures who had been settled in California for hundreds of years.

All this detail, while interesting, sometimes clouds the bones of the mystery, which is an interesting one involving three privileged cousins, any one of whom could be a killer. What’s certain is that all of them are gorgeous and seductively charming, and that they have a grandmother convinced of their innocence. Tying the narrative together is the lengthy and detailed deposition given by the grandmother, who tells the DA that none of her granddaughters are murderous.

The other connecting factor is Al himself, who is fighting against not only a DA who is determined to solve the case, no matter the outcome, and the discomfort he’s felt enforcing the internment rules against his Japanese neighbors. His own Mexican father had been forcibly deported when he was a child, but he seems reluctant to connect his experience to that of the Japanese. He’s also trying to care for his niece, Miriam, whose mother has abandoned her and who, at 11, is basically raising herself. It’s clear she’s a preternaturally intelligent child and that the two of them are very fond of one another.

Chua has created scads of fascinating background and an interesting mystery. While the threads connect, there are just too many of them, and she muddies the waters by changing the culprit several times. The Claremont is a fabulous setting for a mystery, though: a gorgeous, gracious hotel, seeming to float above the hills of San Francisco. This book has atmosphere and character and setting and plot – just too much of all of them. I would be interested to read a second book to see if Chua can winnow and edit. — Robin Agnew