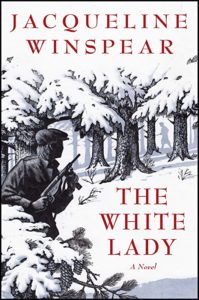

Jacqueline Winspear’s The White Lady spans two wars. Despite this epic scope, the book has the feel of an intimate character study. Luckily, the character at the center of the novel, Elinor White, is well worth a look. As a little girl in Belgium with an British mother and a Belgian father, the book opens as the war begins and little Lini’s father is gone. Somehow, even as a 10 year old, Elinor knows she will never see her father again, so she, her mother, and her older sister, Ceci, form a tight unit, a unit that becomes much tighter during the German occupation of their little village. When a strange woman asks them to help out, the two girls become a part of the resistance.

Jacqueline Winspear’s The White Lady spans two wars. Despite this epic scope, the book has the feel of an intimate character study. Luckily, the character at the center of the novel, Elinor White, is well worth a look. As a little girl in Belgium with an British mother and a Belgian father, the book opens as the war begins and little Lini’s father is gone. Somehow, even as a 10 year old, Elinor knows she will never see her father again, so she, her mother, and her older sister, Ceci, form a tight unit, a unit that becomes much tighter during the German occupation of their little village. When a strange woman asks them to help out, the two girls become a part of the resistance.

Winspear’s careful laying of the groundwork of recruiting resistance fighters and putting them to work was an unusual detail, one I haven’t seen in the war novels I’ve read. It’s fascinating to see how Elinor takes to the work. She’s able to push down her emotions and function – as she is taught – as a predator, with a healthy dose of fear. Ceci doesn’t take to it quite as readily, and one of the puzzles of the book are the two different paths the girls eventually take.

As the book goes back and forth timeline wise, we also encounter Elinor – now a seasoned agent – during WWII, as well as just post war, as London is struggling with gangs. The gangs were another unusual detail, and the only recent literary echo is in Allison Montclair’s excellent series set just post war. Elinor is drawn back into “the life” as she sees it affecting her neighbors, a hardworking mother and father with a sweet little girl. Elinor especially takes to the little girl and there’s a secret there as well, one that’s not unraveled until the end of the novel.

One of the things that really makes this novel stand out is the author’s portrait of Elinor. We see Elinor as a young girl, a sponge, learning the lessons of war from an expert. We see her as an accomplished adult, fulfilling her task of organizing resistance in WWII Belgium. And we see her later, as a traumatized adult, sorting through the ways she’s learned to live with the things she’s done.

The other thread that caught me was the underestimation of women. It starts with Elinor as a young girl – no one would expect her to do the things she does. It’s the women in the marketplace, fighting for a place in the breadline. It’s a secretary. It’s the sister of the gang leader. The true message of this novel might be: don’t underestimate women. And Winspear provides the reader with concrete examples of why you shouldn’t.

And of course, there’s Winspear’s trademark lovely prose, the kind of prose that leads to often reading with a lump in your throat. This is another indelible character from Jacqueline Winspear’s talented pen.